For the first time, we are bracing ourselves for this year’s Juneteenth season. It’s a strange position to find oneself, this discomfort with the new public face of a specific Black holiday you have celebrated for generations in your family. First, there’s delight in the public recognition of Black freedom, survival, and strength, culminating in President Biden signing into law the formal recognition of Juneteenth as a federal holiday last week.

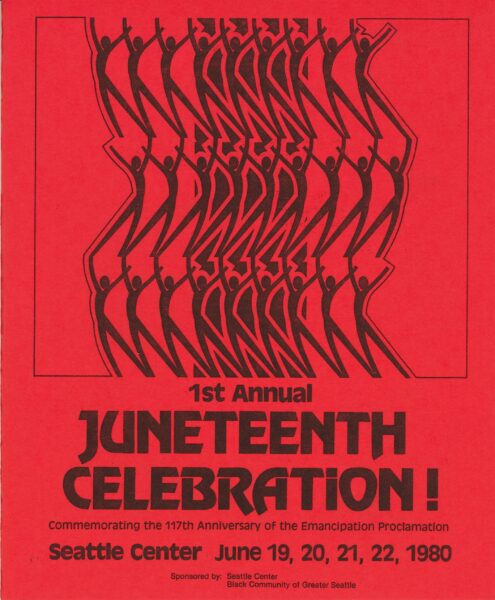

Juneteenth celebrations, like this 1980 event in Seattle, are sacred spaces and should be honored accordingly. Seattle Municipal Archives

But something about this is troubling. In the superficial rush for “racial reckoning” in the weeks following the brutal murder of George Floyd in Minnesota last year, Juneteenth seemed to be caught up in these surface-level patches. Suddenly, non-Black folk were bandying it about, wishing us a Happy Juneteenth, discussing its significance. And there’s something off-putting there.

For over 150 years, Juneteenth was a largely local affair, celebrated by Black Texans and slowly gaining recognition across the country. Juneteenth is an ethnic and culturally specific holiday—it’s Black American—and even more than this, it is regionally specific and tied to enslaved Black American Texans and their descendants. When it comes to the stewardship of this practice, this should be recognized. They are the center, the authors. They should be the “face” and the “voice” of Juneteenth.

Juneteenth has its roots in the reading of the June 19, 1865, announcement of General Order No. 3 by US Army general Gordon Granger, proclaiming freedom from slavery in Texas, a full two months after the surrender of the Confederacy. Much has been made of the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation ostensibly freed, as of January 1, 1863, “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States.” The narrative of the Emancipation Proclamation as a truly liberatory document is, of course, false; rather, the document was a valuable tool in the framing of the larger conflict and the aims of the war. Like the Emancipation Proclamation, this declaration of the end of enslavement on June 19 is not significant for any legal reasons. Instead, it marked a moment from whence Black Texans could stake their claim as free people, simultaneously proclaiming their humanity and importance while also rejecting the idea of being the recipients of political largesse.

For over 150 years, Juneteenth was a largely local affair.

Juneteenth is a culturally specific Black celebration that is also about claiming freedom, embodying it, standing in full humanity. It is a moment celebrated in many a sweaty barbecue or in the simple camaraderie around heavy-laden dining tables. Finally, the holiday trumpets. We are free people. But to that end, it was still a local celebration, one that reflected the fierce joy and powerful reclaiming of destiny and hope—first in Galveston and then more widely in Texas— sentiments not dimmed with the enactment of Jim Crow segregation laws a generation later and in the century of struggle that followed.

Juneteenth is a sacred and special holiday for Black Americans with a specific cultural history and intent. It is a form of freedom-making and freedom-marking that has unique meaning for us that cannot be generalized into a wider celebration of freedom for all people in the United States any more than Diwali or Hanukkah can be generalized into universal appreciations of light in the darkness that can be claimed by anyone.

One of the legacies of enslavement has been the idea that Black people—their bodies, their culture, their work, their livelihoods—are not theirs alone, but communal property. When Black freedom and life-making gets abstracted, and when our struggles become instead an analogy for larger American progress (not unlike the flattening of the Civil Rights Movement as a generic struggle for inclusion that can be applied to nearly anything), we have some of the cruelest forms of cooptation.

Let Juneteenth be a Black experience, our Black experience.

Which returns us to last week’s federal holiday proclamation. This act points to the country’s enduring use of Black people’s visions and articulations of freedom for its own symbolic displays of democracy and exceptionalism. Such a move is performative. Rather than partnering in the ongoing struggle for Black freedom, this bill fails to improve the material, day-to-day lives of Black Americans. Consider that demands for reparations for the unpaid labor of the enslaved in Galveston and beyond remain unaddressed. Further, proposals on the part of parents and school districts to remove opportunities for students to grapple with anti-Blackness, critical race theory, and structures of inequality—such as that of chattel slavery—abound in our nation’s mainstream discourse. The federal government’s commemoration of Juneteenth is a hollow one as long as it refuses to allow the freedom trumpet to sound.

Does this mean that Juneteenth should be forbidden to all non-Black Americans? Of course not. Rather, Juneteenth should be regarded as a sacred Black holiday, one of particular significance with contextual and regional meaning. Juneteenth is not something to be absorbed and abstracted to service broader non-Black aims.

Let Juneteenth be a Black experience, our Black experience. If you are invited to celebrate in our cultural moment, behave as a guest. While we firmly believe that all types of folks can recognize, acknowledge, and teach Juneteenth, there can and should be lines, bounds in the realm of celebration. On this holiday claiming our freedom and space, we ask non-Black Americans to recognize and honor our freedom, our history, and our autonomy. Our freedom is not simply an additional flavoring to add to the hot dusty days of mid-June. It is a sacred space that we ask you honor accordingly.

Channon Miller is assistant professor of history at the University of San Diego; she tweets @channonsmiller. T.J. Tallie is associate professor of history at the University of San Diego; he tweets @Halfrican_One.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.