“These are trend-setting books,” Hirad Dinavari, curator of A Thousand Years of the Persian Book, told me as he pointed out the section of the exhibit on modern Iranian books critiquing contemporary society.

“These are trend-setting books,” Hirad Dinavari, curator of A Thousand Years of the Persian Book, told me as he pointed out the section of the exhibit on modern Iranian books critiquing contemporary society.

This Library of Congress exhibit is about books, but it also tells a history of the Persian language. Ancient Persian was written in cuneiform, Middle Persian is based on Aramaic script, and the Persian in use today is based on Arabic script. Persian was the main language in what is now Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, and it is a language that has been used by many religions, including Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and the Baha'i faith.

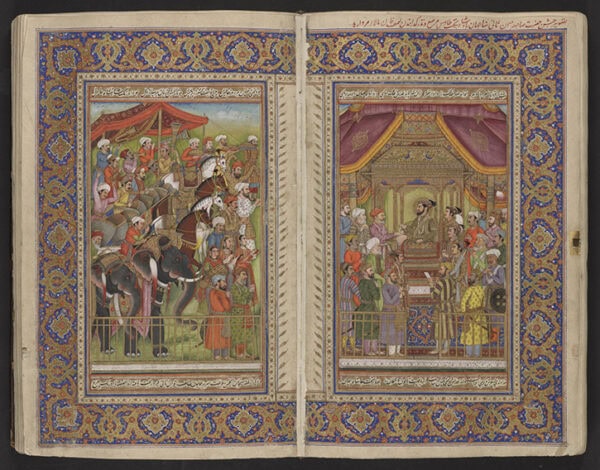

The exhibit contains 75 items that represent pivotal moments in the history of the Persian language and the cultures that used it. Persian was the language of the court of the Mughal Empire in India from 1526 to 1858, and Muhammad Iqbal, considered today to be the father of Pakistani nationalism, wrote poetry in Persian.

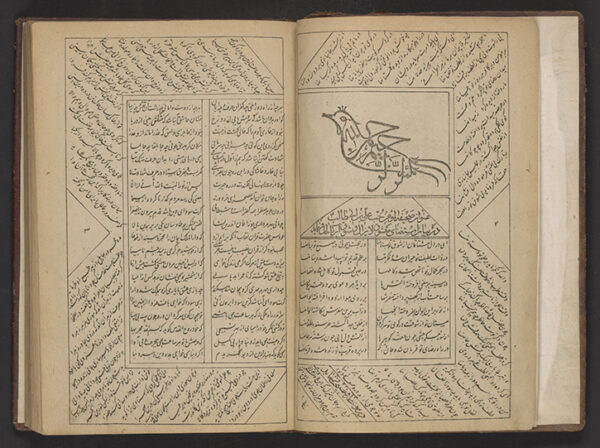

The exhibit also shows how Persian writers responded to changes like the introduction of the printing press, which was brought to the region by Armenian Christians. Persians loved beautiful calligraphy and ornate illustrations, and so were reluctant to have their books printed; they instead used the lithograph for centuries and retained calligraphic script.

Dinavari stressed that he wanted to show how Persian books were both influenced by other cultures (Aramaic, Arabic, Indian, Western) and also influenced other cultures (Indian, Georgian, Turkish, American). For example, TheBook of Shah Jahan, written in Persian, about the king who built the Taj Mahal in India, has Mughal, Safavid, and European influences. The Shahnameh, a story of ancient Persia written in 50,000 couplets divided into 990 chapters, was copied, illustrated, and adapted by many other cultures. The Library of Congress’s oldest copy of the Shahnameh itself is a composite of elements from different times-the text was written in 1618, the illustrations were made fifty years earlier, and the binding is from the 18th century.

A section of the exhibit is devoted to women who wrote in Persian, including the 10th-century Rabi'ah-i Balkhi, who may have written for the same Samanid court the famous poets Firdawsi and Rudaki wrote for; Zebun-Nissa, whose poetry Tajikistanians now consider iconic; and Tahira, who became the symbol of the women's movement and the green movement in Iran.

The exhibit ends with groundbreaking modern books, such as My Uncle Napoleon, a humorous cultural critique that became so popular it was turned into a TV series, and The Cursing of the Land,by Jalal Al Ahmad, who coined the term “Westoxification.”

A Thousand Years of the Persian Book is open until September 20, 2014, and those unable to see it in person can explore it on the Library of Congress website.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.