Workers’ struggles, civil rights, industrialization, railroad development, and urban planning—many 19th-century American stories converge at the Pullman National Historical Park (PNHP) on Chicago’s Southside.

An urban NPS site, the Pullman National Historic Park tells a story of 19th-century labor, business, and city planning. Mike Matejka

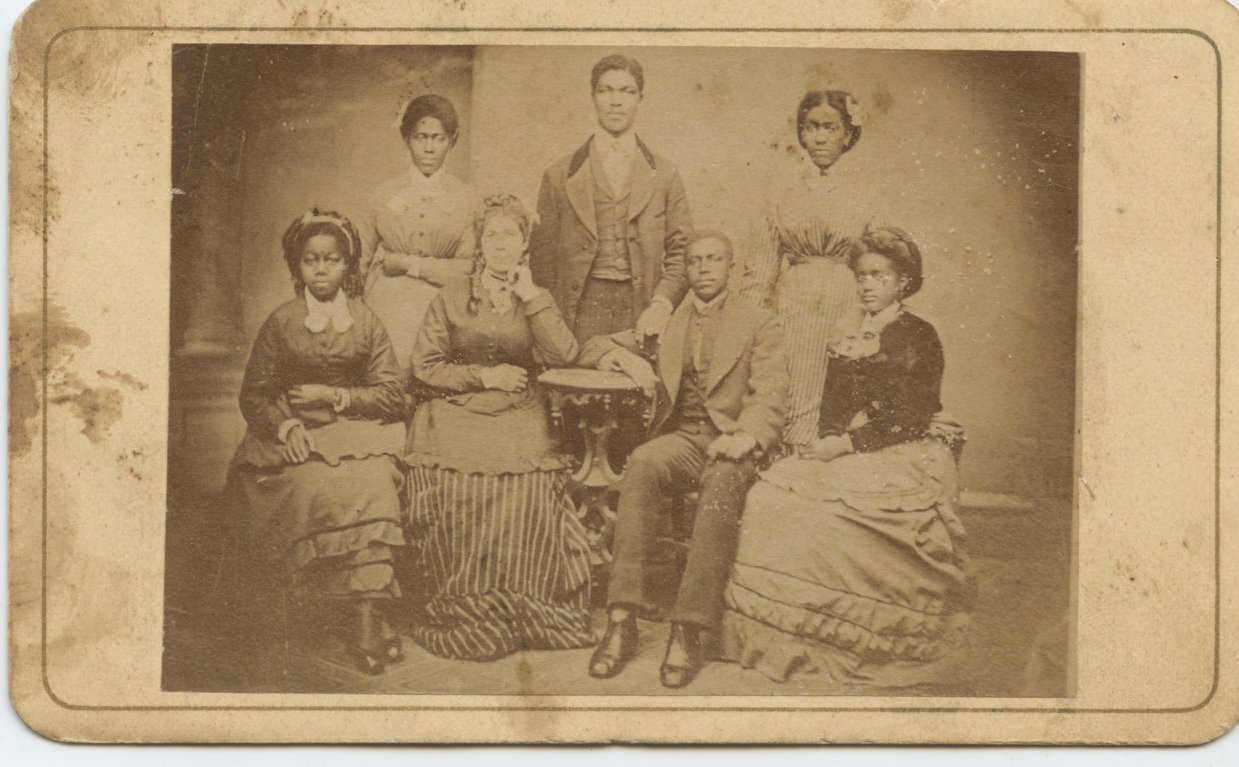

The Pullman Company, founded by entrepreneur George M. Pullman, perfected the overnight railroad sleeping car. Beginning in 1867, these railcars traversed the United States and Europe. The Pullman name became synonymous with high-class travel, with formerly enslaved African Americans serving as Pullman porters.

As his car production expanded, Pullman secretly bought land south of Chicago’s city limits. In 1881, he announced his company town. Pullman, Illinois, included a factory complex, worker housing, stores, and a church. Pullman employed almost 4,000 workers, who not only produced luxury passenger cars but also freight and subway cars, city streetcars, and other rail products. Workers enjoyed superior conditions in Pullman—paved streets, sidewalks, running water, and sanitary facilities. They had everything but democracy in the tightly controlled community. The town was considered a model for corporate benevolence; while Chicago stockyard workers lived in slums, Pullman’s model town offered a stark and positive alternative.

Today, visitors to PNHP can stroll the same streets where factory workers and their families lived for generations, the row houses preserved and many historically restored. PNHP’s visitor center and offices are housed in the town’s 1880s clock tower, which looms majestically alongside one surviving factory wing and the ruins of two others. The State of Illinois is currently seeking bids to restore and operate the Hotel Florence, the company’s 19th-century showpiece. Always conscious of his public image, Pullman the man built Pullman the town as a showcase, reflecting the high standards enjoyed on a Pullman sleeper journey.

They had everything but democracy in the tightly controlled community.

However, that high standard could not be maintained for long. Railcar orders fell in the 1893–94 recession. Pullman prioritized paying shareholder dividends over his workers, cutting wages and hours but not rents. A worker delegation called on Pullman for rent relief. He refused their demands, a misunderstanding at the plant escalated, and workers walked out on May 11, 1894. They joined the newly organized American Railway Union, led by Eugene V. Debs, which held its convention in Chicago that June. After an ARU delegation could not convince Pullman to reconsider, the union delegates voted to boycott Pullman cars, refusing to move any train with a Pullman car attached. By July 4, hardly a train was moving in 27 states.

US Attorney General and former railroad attorney Richard Olney convinced President Grover Cleveland to dispatch federal forces to move the trains. A primarily peaceful strike erupted with confrontations, and at least 30 people were killed. Debs was arrested for restraint of trade and convicted under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The union and the strike were broken, the nation’s most significant 19th-century industrial job action thwarted.

Other Pullman workers made civil rights history. Racially excluded from the all-white railroad unions, in 1925 Pullman porters formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids and invited publisher and socialist A. Philip Randolph to lead their organization. It took 12 years to win a first contract, proving African Americans could lead an effective union. Randolph used the BSCP as a civil rights platform, helping lay the foundation for the Civil Rights Movement in the following decades.

By the 1960s, rail passenger traffic had diminished significantly with the new interstate highways and air travel capturing the traveling public. Work at Pullman slowed and shifted to other plants, while the iconic Pullman Car stopped riding the rails in 1968.

The State of Illinois acquired the factory site and the Hotel Florence in 1991. President Barack Obama declared the site a National Monument in 2015, and Illinois deeded the clocktower site to the Department of the Interior. In 2022, Pullman became a National Historic Park.

A unique urban park, PNHP offers reflections on 19th-century urbanism, city planning, labor, and entrepreneurship. Because the Pullman story is so diverse, the National Park Service has partners to aid interpretation. The park’s official “Friends” group is the Historic Pullman Foundation (HPF), founded 51 years ago as a neighborhood organization. Other partners include the Pullman House Project, the Illinois Labor History Society (ILHS), and the A. Philip Randolph National Pullman Porters Museum, each offering its unique perspectives to visitors.

Because the Pullman story is so diverse, the National Park Service has partners to aid interpretation.

NPS rangers provide tours, complemented by the partner organizations’ efforts. Since Chicago’s Southside is a diverse area, the park makes special efforts to reach neighborhood groups, youth, and schools. HPF also offers tours, a speakers’ series, maintains its exhibit hall, and hosts two annual special events, Railroad Days each spring and House Tour each fall. Currently, there is no Pullman car on site, so HPF is launching an effort to build a rail spur and a suitable building to house vintage Pullman-built equipment. The ILHS offers tours and works with the Chicago Federation of Labor to host the Labor Day Parade through Pullman. The Pullman House Project currently operates a coffee shop in the restored executive Pullman Club and leads tours of both an executive home and a worker’s apartment.

“As historian Wallace Stegner once observed: ‘The national parks are the best idea we ever had.’ He was absolutely right,” said HPF president Maria P. Hibbs. “National Historical Parks preserve not only the built environment in some of our nation’s most consequential places, but more importantly, they tell the very human stories about why these places are important; how they shaped our nation. These lessons must remain alive and conveyed with integrity to inspire the next generation and those that come after.”

As trains rumble by on the adjoining Canadian National Railroad tracks, visitors can walk the neighborhood and immerse themselves at the Visitor Center, which thoughtfully explains and appropriately questions the Pullman legacy. Walking through the restored Workers’ Gate, one can imagine hundreds scurrying to work or home—building not only a transportation legacy, but also sustaining their homes, finding their American voice.

Mike Matejka is a board member for the Historic Pullman Foundation and president of the Illinois Labor History Society.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.