The United States: Self-Taught Activism

In an era when many Americans complain that the political system is not responsive, we might take inspiration from those times in our past when ordinary people came together to transform politics and culture. The Civil Rights and the popular conservative movements of the 20th century attest to the impact ordinary people can have on politics. Traditional political history emphasizes campaigns and elections because a large part of politics concerns gaining and wielding state power. Yet a more diverse set of Americans met in civil society, and from there forced controversial questions onto the public agenda. The story begins in the decades after the American Revolution, when many Americans discovered that by organizing, they could change their neighbors’ hearts and minds and, by doing so, pressure elected leaders to respond.1

In an era when many Americans complain that the political system is not responsive, we might take inspiration from those times in our past when ordinary people came together to transform politics and culture. The Civil Rights and the popular conservative movements of the 20th century attest to the impact ordinary people can have on politics. Traditional political history emphasizes campaigns and elections because a large part of politics concerns gaining and wielding state power. Yet a more diverse set of Americans met in civil society, and from there forced controversial questions onto the public agenda. The story begins in the decades after the American Revolution, when many Americans discovered that by organizing, they could change their neighbors’ hearts and minds and, by doing so, pressure elected leaders to respond.1

Civil society is that space not part of the state, the private realm of family and friends, or business, where people emerge from their individual lives to promote public goods together. Civil society did not just naturally evolve in the new nation. Americans had to learn to organize.

Ministers were among the nation’s first grassroots organizers. Although associations had existed before the revolution, after independence they spread outward from cities to rural areas and expanded their reach to a broader swath of Americans. In town after town, ministers encouraged congregants to provide charity, to distribute Bibles, and to fight such vices as intemperance. Forming an association required drafting a constitution, electing officers, soliciting members and dues, and then acting locally. Although these seem like small things, as more and more Americans learned to do them, they transformed the country’s civic landscape.

Ministers also relied on print to spread knowledge about associating. Newspapers and pamphlets publicized work done nearby, inspiring others to follow suit. The circulation of associations’ annual reports and their republication in the press encouraged citizens to donate time and money, and to form local chapters, much like organizations’ newsletters do today. Association leaders learned to write annual reports for public consumption rather than just for one another. In 1813, the Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance’s board of directors had simply “submitted and accepted” its annual report; by 1826, the directors were printing 6,000 copies. These reports offered citizens a template to follow when they decided to organize.

As more Americans formed associations, organizers focused their lobbying on fellow citizens, not just elites. One can see the shift in the two phases of the effort to prohibit US mail delivery on Sundays (the Sabbatarian movement). At first, it was a top-down affair. Ministers distributed petitions calling on Congress to stop Sunday mail delivery and solicited signatures in their churches; by 1815, about 100 petitions had reached Congress. In 1828, however, the General Union for Promoting the Christian Sabbath directed its energy to shifting “public sentiment,” or public opinion. Members urged other citizens to take stands on important issues and to put pressure on one another. Americans formed local chapters, and by 1829, 467 petitions reached Congress. By 1831 the number had topped 900.

Americans applied their newly acquired civic skills to new causes. People from around the world were amazed. Alexis de Tocqueville, visiting the United States from France, wrote in his two-volume Democracy in America (1835, 1840) that “Americans of all ages, all conditions, and all minds are constantly joining together in groups.” In Europe, Tocqueville wrote, it took a noble or a lord to get things done. In the new United States, people mobilized themselves. Of course, equality was never absolute. The well-off and well-connected had more political influence than most Americans, but Tocqueville realized that when ordinary people came together, they amplified their voices. “Thus the most democratic country on earth is the one whose people have lately perfected the art of pursuing their common desires in common and applied this new science to the largest number of objects,” Tocqueville wrote in awe.2

From temperance and prohibition to anti-Catholicism or labor rights, Americans used associations to shape public conversations. They brought forward causes that politicians would have preferred to keep out of politics—especially antislavery. After the revolution, Benjamin Franklin and other elite members of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society had petitioned Congress to end slavery, and their appeals were received politely by their peers. By the 1830s, however, ordinary Americans, black and white, would make their voices heard through what historian Richard S. Newman calls a “mass action strategy.”

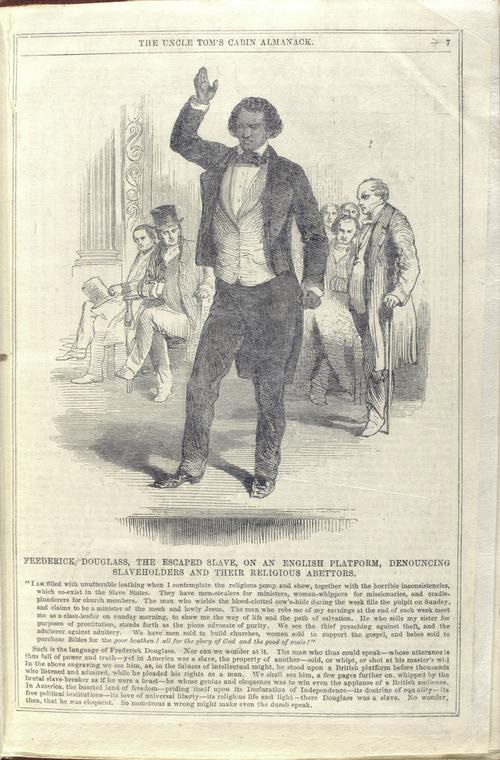

Black Americans ensured that antislavery remained on the public agenda. Through churches, fraternal associations, and charities, they developed a network of institutions that spoke among and for themselves. These networks enabled organizers to circulate petitions calling for the end of slavery and discrimination. By the 1820s, African Americans had formed antislavery societies, hosted conventions, and published pamphlets and newspapers publicizing slavery’s evils and calling for its abolition. These networks provided not just the ideas but the money for white editor William Lloyd Garrison to start his newspaper, The Liberator, which would become the nation’s most prominent abolitionist publication. In its first year of publication, 450 of its 500 subscribers were black.3

Garrison represents what ordinary citizens, as part of organized movements, could accomplish. Nothing in Garrison’s background suggested that he would become America’s most famous white abolitionist. He was born in 1805 in Newburyport, Massachusetts, into the middling ranks. After his father left, his family struggled, and Garrison grew up poor. In 1818, he became an apprentice at the Newburyport Herald, joining America’s newspaper trade. He also became committed to antislavery. By the late 1820s, he was ready to act. He published The Liberator’s first edition in 1831. With black and white citizens, he helped establish the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832, which held its first meeting in the basement of a black Baptist church in Boston. The new society sent agents from town to town, exhorting people to organize antislavery chapters, to host lectures, and to speak out. Public opinion began to change.

Among citizens’ most powerful tools was the petition. Earlier petitions had appealed to the king, reinforcing subjects’ dependence on their sovereign. Citizens turned petitioning into a democratic instrument to exert pressure from below, reminding elected leaders who was now in charge. Moreover, petitioning brought Americans into politics. People volunteered to circulate petitions and, by signing, claimed a voice in the public sphere, an especially important action for Americans denied the vote. Petitions with dozens to hundreds of signers told elected leaders where public opinion was headed. They also demonstrated that Americans considered public opinion something they produced rather than something to consume, as we do polls today. Abolitionist Wendell Phillips proclaimed, in 1852, that public opinion was forged not just in statehouses but “in the school-houses, at the hearthstones, in the railroad cars, on board the steamboats, in the social circle,” and, of course, “in the Antislavery gatherings.”

Their efforts were working, we know, because other Americans responded by trying to silence them. Printing presses were torn down. A mob once led Garrison out of a Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society meeting with a noose around his neck. Another mob threatened to burn down a building where Sojourner Truth was to speak. When antislavery societies sent their literature down south, southern slaveholders sought to censor the mail and even urged northern leaders to shut down antislavery organizations. Words mattered, and the words of people organized for change mattered even more. Despite the best hopes of party leaders who sought to keep slavery out of politics in order to maintain their national coalitions, black and white northerners, both women and men, forced the slavery question onto the public agenda.

Women eventually became voters through their activities in civil society. With the exception of New Jersey, where propertied women could vote until after the 1807 election, women lacked formal political power. But they could organize. Issues women cared about—temperance, opposition to Indian removal, antislavery, and female suffrage—entered public debate thanks in large part to their own efforts. Women who had learned to organize by participating in the antislavery movement argued that an egalitarian society must enfranchise not just all men, but all Americans. Like antislavery activists, 19th-century suffragists pooled time and resources, formed local chapters, hosted lecturers, held conventions, distributed print literature, and petitioned elected leaders. And through these efforts, woman suffrage was put on the table.

It was in civil society that some of the issues that matter most to Americans today concerning racial and gender equality entered our public conversations. This is not to deny or diminish the role of political elites or political parties. The point is that by organizing themselves, ordinary people discovered a way to be part of American politics and ensured that our political history would be as diverse as the nation. And, by doing so, they enriched our political debates. They remind us that in a democracy, citizens should shape public opinion instead of allowing public opinion to be something that is measured and manipulated from above. Garrison hoped that this would be a legacy of the antislavery movement. In 1873, he wrote, “battles yet to be fought” would rely on “the means and methods used in the Anti-Slavery movement.” And since Garrison’s time, Americans of all political persuasions have done so.

Johann N. Neem is professor of history at Western Washington University. He is author of Creating a Nation of Joiners: Democracy and Civil Society in Early National Massachusetts (Harvard Univ. Press, 2008) and is completing a book on the development and purposes of public education in the United States.

Notes

1. This essay draws from my more detailed discussion “Two Approaches to Democratization: Engagement versus Capability,” in Practicing Democracy: Popular Politics in the United States from the Constitution to the Civil War, ed. Daniel Peart and Adam I. P. Smith (Charlottesville: Univ. of Virginia Press, 2015), 247–79.

2. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2004), 595–99.

3. Richard S. Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2002); Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Tags: Perspectives on Democracy North America

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.