Accuracy and Authenticity in a Digital City

Slave Streets, Free Streets and the Landscape of Early Baltimore

Imagine strolling through Baltimore 200 years ago. The narrow, unpaved streets lead you past public markets and taverns, grand mansions, and tiny alley houses. The Federal Hill observatory towers over the harbor, its shipyards, and its wharves. As you leave the tightly packed streets near the water, the houses become farther apart, interspersed with the jail, a hospital, a seminary, an almshouse, long ropewalks. You pass fields and gardens, patches of forest and orchards. The virtual landscape in which you are immersed—because, of course, you have not traveled back in time—is beautifully textured and lavishly detailed, a Google Street View for the past.

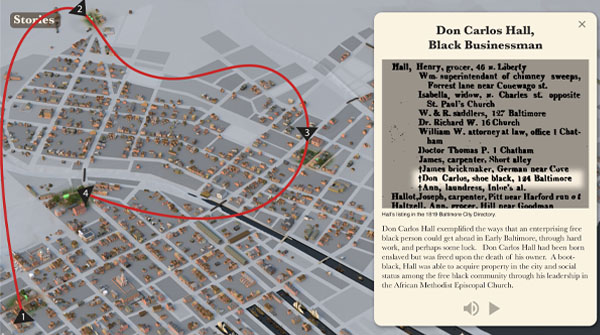

This view from Slave Streets, Free Streets shows Don Carlos Hall’s route from his shop on Baltimore Street to his manufactory, to his home, and then to Bethel AME Church. Courtesy Lee Boot

This is the digital world created between 2012 and 2014 by Visualizing Early Baltimore. A collaboration between the Maryland Historical Society and the Imaging Research Center (IRC) at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), led by Dan Bailey, the project combines historical research with cutting-edge modeling and mapping technologies to build an accurate 3D model of the city and its terrain, land use, and buildings circa 1820. The BEARINGS of Baltimore (as this first phase is called) is a 2.5-billion-pixel bird’s-eye view of early Baltimore. IRC computer programmers have made this scene navigable online and by touch screen, allowing users to zoom into the details of the city. Developers built the scene on accurate topography, drawing on historic maps, architectural histories, historic documents, and period art, as well as consultations with urban and architectural historians. Extant and known buildings were modeled and textured, the landscape filled out with representative buildings placed carefully. The streets are carefully aligned according to period maps and descriptions. The team believes that this visualization is as accurate a recreation as can be made. It draws viewers into the past, allowing them to make easy connections with the present (for example, many of Baltimore’s public markets remain at the same locations).

I became involved in the project in 2014, when Dan Bailey showed it to me, and I was so enchanted that I insisted he include me in future collaborations. What I saw was, in Dan’s words, “a beautiful stage set.” But there were no people on the streets, no context describing early-Republic Baltimore in all its vibrant, problematic complexity, as described by historians like Martha Jones, Christopher Phillips, and Seth Rockman. There was no sign of the new immigrants from Europe and relocated country folk pouring into the city. The enslaved people who worked alongside free blacks and whites in the city’s shipyards and construction sites were similarly absent.

We decided to focus our expansion of BEARINGS on the lives of Baltimore’s free blacks and enslaved workers in a project called Slave Streets, Free Streets: Visualizing the Landscape of Early Baltimore. By highlighting the embedded landscape in which approximately 4,300 enslaved and 10,300 free African Americans lived and worked, users see how slavery was enmeshed in the world of early Baltimore, even though the city appears far more integrated than it is today. It reminds us of the degree to which racial slavery and early capitalism combined to limit opportunities for African Americans. Finally, it allows us to put faces and names to the largely anonymous ordinary people of the past. On a methodological level, we are making an argument about the power of visualization as a storytelling medium, to show how mapping can spatially illuminate relationships of power and place.

In this project, we look at three interrelated groups of people represented in different map layers: free blacks, enslaved workers, and fugitive slaves, as well as the sites and workings of the slave trade. Drawing on city directories, tax and census records, newspapers, and other historical documents, we have placed people—both free and enslaved—around the city, tying them by name to specific addresses. We have identified dozens of places where Baltimoreans were engaged in the slave trade, showing the degree to which it was enmeshed in the world of the city. We have also told the stories of fugitives from slavery by drawing on runaway slave advertisements and slave narratives.

The virtual landscape is beautifully textured and lavishly detailed, a Google Street View for the past.

Doing this kind of detailed reconstructive work raises questions about privileging the accuracy of small details at the expense of portraying larger historical themes. Does it matter that the bricks are laid in the correct pattern if our historical interpretations are unsound? Can we use the beauty of our reconstructed landscape to tell the ugly stories of slavery and racial discrimination? We believe that we can.

Don Carlos Hall has such a story, one that benefits from a spatial interpretation. Hall was best known as one of the founding members of Bethel AME Church, Baltimore’s most important African American house of worship. The church was founded in 1816 and met in Hall’s home until it moved into its own building. As Ethel Russaw notes in Call the Roll, Hall was appointed the church’s first book steward and was a member of the committee that wrote the church’s 1820 hymnal. He was born enslaved but was freed upon the death of his owner. Hall worked as a bootblack but was able to acquire property in the city and social status among the free black community.

Unlike many of the free black people whose names elusively appear once or twice in our sources, Hall appeared in multiple documents, and we can imagine his movements around the city. He owned a house on Salisbury Street, near Exeter Street, surrounded by white and black neighbors, including white carpenters, sea captains, widows, and a town watchman, as well as free black laborers, waiters, and laundresses. Seven people lived in the Hall household in 1820: Hall and an adult woman, probably his wife, and five free black boys under the age of 14, perhaps his sons or a combination of family and young apprentices. But Hall also had a daughter who was enslaved in Louisiana, and according to his will, he died without being able to purchase her freedom.

Hall had a bootblacking stand (essentially a shoe-shine stand) in the basement of 124 Baltimore Street, below Marmaduke Wyvill’s merchant tailor shop. Shoe and bootblacking were occupations dominated by free black men; there are no white practitioners of these trades listed in the 1816 city directory. We can imagine Baltimore’s merchants and gentlemen stopping in the shop to have their new clothes fitted and then get their shoes polished, perhaps sharing news and gossip while they waited.

In addition to his home on Salisbury Street, Hall owned a two-acre parcel of land farther out from downtown on New Harford Road where he manufactured his polishes and varnishes. He appears to have purchased the plot from Philip Rogers, who sold land to two other African American men, gardener Mordecai Chalk and carpenter Joseph Gale.

Our representations are historical asymptotes, approaching reality but never actually reaching it.

On any given day, Hall would have walked from his home to his shop, and then perhaps out to his manufactory or over to Bethel AME Church. Baltimore Street, where Hall’s shop was located, was the heart of early Baltimore's commercial district. It was lined with merchant houses, dry goods stores, confectioners and millinery shops, silversmiths, and booksellers. If Baltimoreans wanted to buy food and luxury goods from all over the world, Baltimore Street was where they shopped. Baltimore Street was also inextricably linked to the institution of slavery. In 1818, 123 enslaved people, owned by 54 different whites, lived and worked on Baltimore Street. And, because the city did not have a central slave market, Baltimore Street was also a site of the slave trade. Between 1815 and 1820, scores of men, women, and children were bought and sold—singly and in large groups—in Baltimore Street taverns and merchant houses. Hall would have seen all of this.

Our team has created a series of visualizations showing Hall’s likely movements around the city, highlighting each place he would have visited. The visuals counter the idea that early Baltimore was rigidly segregated spatially, instead graphically illuminating the ways in which the city was a place of fluidity and movement. Our beautiful stage set can come alive.

Yet there are limits to our visualization. While we use the metaphor of adding people to our reconstructed city, we can only represent them abstractly. In part, this is because creating realistic human avatars is still a very labor-intensive, and consequently expensive, process. But we also don’t want to pretend that we know what people looked like 200 years ago. We worry that our project gives an illusion of greater certainty and fixedness than we really have, and images of actual, physical people would contribute to that in an unhelpful way. Instead, we use colored dots. Our representations are historical asymptotes, approaching reality but never actually reaching it. We have decided, for example, that we will put people without a detailed address on the streets themselves, as though they were walking to and from work or home, representing them in their neighborhood worlds. In this way, we believe we can best balance the known and the unknown, not being afraid to admit that there are, and will always be, gaps in our knowledge of the past.

Gaps notwithstanding, immersion into this deep visualization will remind users that the issues of the past still resonate in the present, and that ordinary people shaped their own lives, spaces, and legacies. We hope, too, that the project inspires related work, using our stage set to tell a variety of stories.

Anne Sarah Rubin is professor of history at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She tweets @AnneSarahRubin.

Tags: Features Research Digital History North America African American History Public History

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.