Historian of Black America

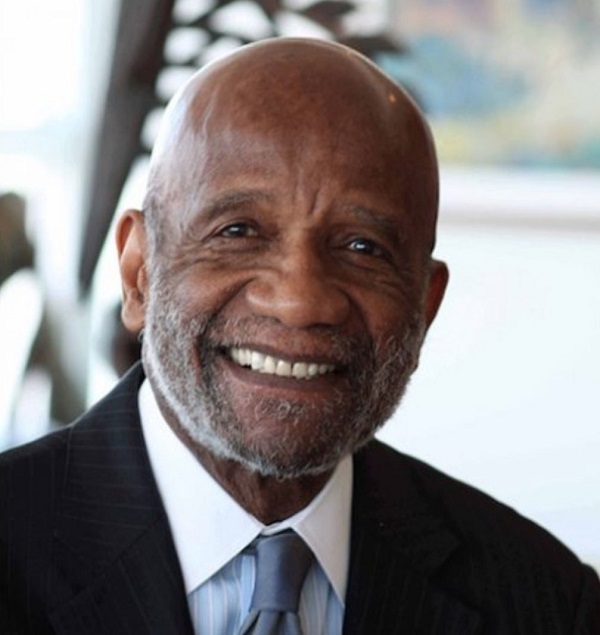

The historian and journalist Lerone Bennett Jr. passed away on February 14, 2018, at age 89. Born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, he and his family moved to Jackson when he was young. An avid black reader in the age of white supremacy, he had the good fortune of finding a white used-book seller who allowed him to read when the store was closed. His love of history took a serious turn when he discovered a volume of Lincoln’s writings and speeches that challenged the image of the Great Emancipator. A revisionist historian was born.

The historian and journalist Lerone Bennett Jr. passed away on February 14, 2018, at age 89. Born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, he and his family moved to Jackson when he was young. An avid black reader in the age of white supremacy, he had the good fortune of finding a white used-book seller who allowed him to read when the store was closed. His love of history took a serious turn when he discovered a volume of Lincoln’s writings and speeches that challenged the image of the Great Emancipator. A revisionist historian was born.

At Morehouse College, Bennett majored in history, graduating in 1949. After serving in the Korean War, he began his career at the Atlanta Daily World, but before long joined Johnson Publishing Company in Chicago. He worked first for Jet and then for Ebony, becoming the executive editor in 1958. Bennett’s close relationship with company owner John H. Johnson underwrote the journalist’s historical ambitions. With a circulation that peaked at 2 million, Johnson’s Ebony and his book division made Bennett’s works common in black homes.

During the 1960s, Johnson’s editor became the black community’s historian. In 1961, amid the Civil Rights Movement, Bennett authored a popular black history series in Ebony that became the basis for his general history, Before the Mayflower (1962). Historian Benjamin Quarles noted “its unusual ability to evoke the tragedy and the glory of the Negro’s role in the American past.” In 1964, Bennett wrote a biography of his Morehouse classmate: What Manner of Man: A Biography of Martin Luther King. He told the story of the first blacks to exercise political power in Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction 1867–1877 in 1967. The following year brought Pioneers in Protest.

Bennett was much more than a popularizer. He captured the zeitgeist of the black baby boomers and led the shift from “Negro” to “black.” His books brimmed with militant black people who questioned the promise of America and protested their treatment, displacing the patient, patriotic Negroes who longed for citizenship. Before young scholars could come out of the archives and focus on the black protest tradition, Bennett had culled the secondary literature and printed primary sources, and put the new interpretations before the black public. He became a beacon for young scholars associated with the Black Power generation.

When he returned to his initial interest in Lincoln, Bennett found a much less receptive public, especially among academics. In 2000, Johnson Publishing released Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream. For years, he had treated Abraham Lincoln as a white supremacist, but now he viewed Lincoln’s every act to advance black freedom and equality as a grudging concession to reality. Negative reviews followed, and few treated his work as a needed corrective. While Bennett relished his engagement with the overwhelmingly white community of Lincoln scholars, he prized both support of and opposition to his views from within the black community. He spoke most fondly of his black readers who would see him on the speaking circuit and wholly reject his interpretation of Lincoln, as theirs was the view he sought to challenge his entire life.

Bennett’s scholarly home was the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, founded by Carter G. Woodson more than a century ago. Not surprisingly, Bennett played a leading role in changing “Negro” in the association’s name to “Afro-American” in the early 1970s. Like John H. Johnson, who served on the board in the 1950s, Bennett used his renown to support the association. In the early 1980s, he served as vice president, and in the mid-1990s as a council member. In 2003, the association awarded him its most prestigious scholarly award, the Woodson Medallion.

Daryl Michael Scott

Howard University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Tags: In Memoriam African American History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.