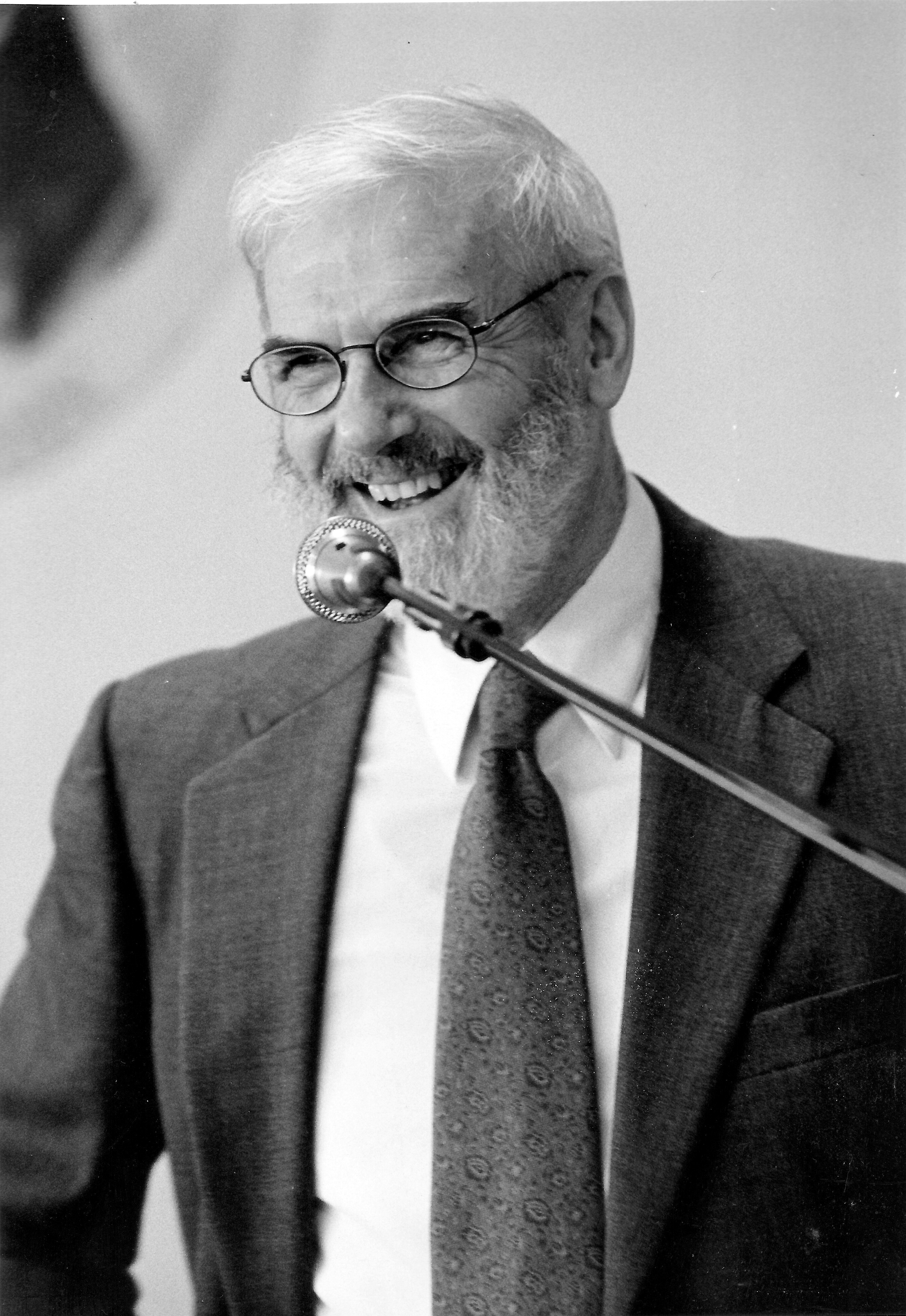

Jonathan Spence, a pathbreaking historian of China and former AHA president, died on December 25, 2021, from complications of Parkinson’s. Jonathan received his PhD from Yale University in 1965 and taught there until retiring in 2008. His numerous honors included a MacArthur fellowship and 10 honorary degrees. His many books, typically told through a biographical lens, showed us Ming intellectuals, Qing emperors, and 20th-century revolutionaries but also brought to life forgotten people; one celebrated book, The Death of Woman Wang (Viking Press, 1978), used just a few fragmentary sources to re-create the world of a peasant woman murdered by her husband in an impoverished 17th-century county. His wonderfully readable textbook, The Search for Modern China (Norton, 1990), emerged from his lectures in what was, year after year, one of Yale’s most popular courses.

At a 2009 conference honoring Jonathan’s career, several of his former graduate students raised an odd question: Had we been scared of Jonathan while studying with him? Nobody thought that he ever tried to be intimidating, but some nonetheless recalled that they couldn’t help being overwhelmed by Jonathan’s accomplishments, feeling they would never measure up. What spared the rest of us, we concluded, was that what Jonathan did was so inimitable that nobody could expect us to match it—leaving us free to be whatever kinds of historians we could be, with the full support of an adviser who never gave any hint of wanting anything else. Jonathan’s enthusiastic engagement with dissertations ranging from art and philosophy to number-crunching social and economic history was, I now realize, extraordinary, but at the time I took it for granted: that was, apparently, what great historians did.

This seemed to flow naturally from Jonathan’s positive attitude toward all sorts of things—from great poetry to less-than-great pizza—rather than being something he explicitly theorized. But it did, I think, reflect a view that historians, like novelists, should re-create a world, and that whatever would have mattered to somebody in that world was worth exploring. He wrote and taught history to create empathetic understanding, and he knew that fostering such understanding across the great gulf in time and space separating his readers and listeners from most of his subjects required not stripping out the “exotic” to get at something more “universal”—much less isolating independent variables—but showing how, since we all live in particular times and places, what we perceive as the exotic and the universal are always intertwined. For the same reason, Jonathan was committed to what one might call 360-degree teaching, aiming for the kind of fully rounded understanding that history—being, like Jonathan, eternally eclectic—prizes. While not a particularly directive adviser, he did insist on broad preparation. He did not want students neglecting either “old” fields like military history or “trendy” ones like gender history, and I think he was especially pleased when somebody brought seemingly disparate fields together (as the history of masculinity might link these examples).

This commitment to thick description made Jonathan very much a part of his scholarly generation’s project of creating what Paul Cohen called “China-centered” Chinese history. True, he wrote more about individuals than about the big trends of demography, commercialization, and so forth that his contemporaries used to give Chinese history a Chinese motor (replacing “Western impact” as the source of Chinese modernity). True, also, that foreigners featured prominently in his work. But he always emphasized the Chinese context within which they acted and how it shaped them (while questioning how much they shaped China). So, too, he emphasized understanding how these foreigners looked to their Chinese counterparts at least as much as the easier task of reporting how China looked to them.

Fifty years ago, very few Westerners had experience in China, spoke Chinese, or read much from there. Of course, even scholarship like Jonathan’s, which reached audiences far beyond the academy, is only a small part of why so many Westerners now know so much more about China. But it was hardly inevitable that geopolitical and economic entanglement alone would stimulate serious engagement with Chinese culture, or that many people’s engagements would go beyond seeking pragmatic, managerially useful knowledge (already an ambitious goal) to also seek intellectual enrichment and perspective on their own cultures. Jonathan did as much to encourage that broader, deeper engagement as any one person could.

Kenneth Pomeranz

University of Chicago

Tags: In Memoriam Asia/Pacific

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.