Researching the Quinceañera

My Graduate Internship at the National Hispanic Cultural Center

From May 2015 to October 2015, I worked as an intern for the National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC). Opened in 2000 and located just south of downtown Albuquerque, the NHCC serves as a community center and forum for Hispanic art, dance, music, film, and history. It houses an art museum, language center, and several theaters. The new executive director, Rebecca Avitia, wanted to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the NHCC with quinceañera-themed events throughout the year. The quinceañera, or the traditional coming of age party for Hispanic women turning 15 celebrated throughout Latin America and the United States, was a metaphor both Rebecca and her art museum director, April Boroquez, felt they could use to engage the Albuquerque Hispanic community in the 15th anniversary celebration. Rebecca and April envisioned a large quinceañera-themed community party where they would unveil the 15th anniversary art museum exhibit highlighting their permanent art collection.

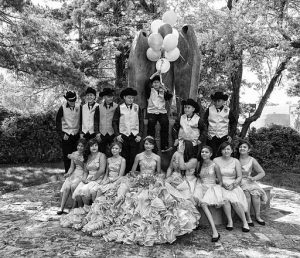

A quinceañera in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Christopher Michel/Wikimedia Commons CC 2.0

I found the internship through the AHA Career Diversity program in the history department at the University of New Mexico (UNM). While I was initially skeptical of the AHA Career Diversity initiative, especially the idea of graduate student internships, my reticence diminished after attending a department-organized session that featured prospective employers from Albuquerque pitching internships to graduate students. After some convincing, and talking with April and Rebecca about the interesting research and work that I could do for them, I decided to pursue a position at the NHCC.

Rebecca and April wanted an intern from the history department at the University of New Mexico to help historicize the quinceañera. Ever conscious of community criticism and response, they wanted to be aware of any historical fault lines hidden within the quinceañera’s somewhat murky history. What were the origins of the quinceañera? Did the tradition stem from Spanish colonization, Native American marriage rites, or the 19th-century Mexican elite? The answers to these questions were unknown to both April and Rebecca, and seemingly only somewhat known to the families celebrating the tradition. Rebecca and April wanted to inform themselves about the tradition, as well as educate the larger community. As their intern, or research associate as I termed it, I had several responsibilities. First, I had to research and put the modern-day quinceañera in its historical context. Second, I had to present my research at the quarterly staff training. Third, and finally, I had to help put on a community event, such as a lecture or a roundtable, about the contested meanings (social, cultural, economic) of the quinceañera.

There were certainly some ups and downs during the entire experience. I particularly excelled at doing the historical research on the quinceañera. Gender history, social history, cultural history, Chicana/Chicano history, and economic history were all possible avenues that April and Rebecca wanted me to explore. I relied heavily on prior graduate school coursework and research experience to keep the project moving at a reasonable pace. Language and translation was a major obstacle, since so many of the important sources are written in Spanish. Yet, I surprised myself with how ready I felt to tackle historical Spanish language documents, a skill honed entirely by and for a history graduate school education.

One of the reasons the NHCC appealed to me was because it offered me the opportunity to improve my public history skills. I had no experience working in conjunction with a museum, and very little experience planning community events. Although the staff training went very well and was well attended, the community event was the opposite. The day of the event dawned rainy and overcast and what was supposed to be a gathering of community members, with April and myself leading a discussion about the modern connotations of the quinceañera, ended up with April and me hanging out in the museum space. The community event flopped for a couple probable reasons: the weather for one; a large arts and crafts fair was happening at the same time, and it probably drew away much of our potential audience; and finally because the NHCC had hosted a full calendar of events for its 15th anniversary in the weeks prior. Visitors may have been burned out on the 15th anniversary theme, or may have just wanted to stay out of the rain. I had forgotten that public historians must compete for, of all things, public attention. April wasn’t too concerned about the lack of audience. She understood that sometimes events are unsuccessful, but that did not mean that the work was bad or not valuable.

Of all the events I participated in at the NHCC, the staff training was probably the most nerve wracking, but also the most worthwhile. I had to condense my research on the quinceañera and explain its historical antecedents, its significance, and how it changed over time to an audience of NHCC employees. This might sound like giving a conference paper, but only if the audience at the conference had personal, first-hand knowledge about the topic of the paper. Many of the NHCC employees had been to a quinceañera, had family traditions surrounding the quinceañera, and probably been the quinceañera (quinceañera is both the name of the party and the name of the 15-year-old celebrant). I was worried that I wouldn’t be taken seriously, but, thankfully, I was proven wrong. After asking for some advice from my advisor and AHA Career Diversity faculty lead at UNM, Virginia Scharff, I learned how important it is to acknowledge, before anything else, the community knowledge that exists within a specific cultural group. I wasn’t upending their experiences or telling them that they were wrong, just adding another dimension to their understanding. In many ways this project wasn’t just collaboration between the museum director and me, but a larger collaboration between the NHCC staff and the community they belong to and serve. Specifically for me, I left the staff training feeling much more confident in not only my research, but in my ability to speak to a diverse group of people, something that will undeniably help in my future career. During the training itself, it was most gratifying when different staff members shared their personal experiences of attending quinceañeras and compared those experiences with the historical information in my presentation.

Historians have always known about the possibilities of applying their skills outside of the academy. My work at the NHCC reminded me that studying history more than just trains you in an academic discipline. It also equips you with a set of practical skills that can be applied to a multitude of professions. Definitely after this internship I think more often and more deeply about how I can harness my history skills in a meaningful way in a possible career outside of the academy. I think about the possibilities of researching for a company or a nonprofit, or working in museums or cultural centers, or synthesizing and analyzing information for a variety of organizations. After my experience, there is certainly more hope for this historian’s future.

The AHA’s Career Diversity for Historians initiative seeks to better prepare graduate students and early career historians for a range of career options, within and beyond the academy. “Historians in Training” features graduate students working in diverse settings and exploring career prospects along the way.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Margaret DePond is a PhD candidate in history at the University of New Mexico. Her dissertation explores the relationship between the beach and gender in American culture in the early 20th century. She is also managing editor of the New Mexico Historical Review.

Tags: AHA Today Career Diversity for Historians Resources for Graduate Students Cultural History Latinx History Graduate Education

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.