What's in the April 2012 AHR?

The April 2012 issue of the American Historical Review should soon be appearing in members' mailboxes and on library shelves; its online version will be available sooner for members and subscribers. In it readers will find five articles on subjects that range chronologically from the Middle Ages to the 20th century and topically from medieval scholasticism and disputes over property in 18th-century North America to U.S. politics after the Civil War, the slave trade in the 19th-century Mediterranean, and African art in interwar Paris. There are also three featured reviews followed by our extensive book review section. "In Back Issues" draws attention to articles and features in the AHR from 100, 75, and 50 years ago.

In "Toward a Cultural History of Scholastic Disputation," Alex J. Novikoff tackles one of the most fundamental and characteristic features of medieval learning, arguing that it had large implications for the cultural history of the period. He begins by examining how scholastic disputation has traditionally been examined, its relation to the form of the dialogue, and how the two might be examined together in light of such disputation's far-reaching effect on medieval society. Deploying an array of source material from the 11th to the 13th century, the article distinguishes five elements of a medieval culture of disputation, ranging from the monastic environment of Anselm and his followers to polyphonic music, debate poetry, and Jewish-Christian disputations. In examining how dialogue escapes its literary origin and passes from an idea prevalent among few to a cultural practice among many, Novikoff offers a mode of cultural history based on the passage of ideas into practices.

"Commons and Enclosure in the Colonization of North America," by Allan Greer, highlights the importance of common property for Spanish, English, and French settlers of colonial North America, as well as for the indigenous peoples they displaced. Whereas many historians, following the lead of John Locke, tend to equate colonization with the privatization of an open commons, evoking something resembling an overseas extension of the enclosure movement, Greer argues that a colonial commons in various guises played a central role in wresting control of land from the possession of Natives. In New Spain, New England, the Chesapeake, and, to a much lesser degree, New France, livestock ranged freely, much to the detriment of Indian property and Indian subsistence. The confrontation between the indigenous commons and the colonial commons typically resulted in the triumph of the latter, thus clearing the way for a later stage of enclosure and settler private property in land. While Greer focuses on the early modern period, he also suggests that a similar pattern of clashing commons can be discerned in the 19th-century histories of South Africa, Australia, and the western plains of North America.

In his article, "The Mexicanization of American Politics: The United States' Transnational Path from Civil War to Stabilization," Gregory P. Downs argues that postbellum history is not a time of reconciliation and stability but rather a period haunted by fears that the end of the Civil War might only lead to more civil conflict. This concern was expressed in a now forgotten but then common discourse evoking the historical example of Mexico as a harbinger of permanent instability as the result of civil war. Recasting the contested 1876 U.S. presidential election as a process of stabilization, the article recovers the prevalence of the Mexican example, which served both to give voice to popular anxiety and to coax politicians toward a peaceful resolution of the crisis. By evoking contemporary fears of the possibility of state collapse, Downs provides an image of a strangely vulnerable 19th-century United States. His article also critiques conventional nationalistic accounts that have—paradoxically—sought to use the history of the Civil War to prove the impossibility of future civil wars. Finally, "The Mexicanization of American Politics" suggests the relevance of transnational history to the study of domestic politics.

In "The Children of the Desert and the Laws of the Sea: Austria, Great Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mediterranean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century," Alison Frank shows that Austrian ships were used by slave traders to transport enslaved Africans from Alexandria and other African ports to Constantinople and other Ottoman cities on the Mediterranean from the 1840s through the 1870s. Although Ottomanists and Africanists have long known that the Mediterranean was rife with slaving throughout the 19th century, its history has been largely overshadowed by the story of the Atlantic slave trade on the one hand, and 19th-century abolitionism on the other. Frank thus suggests a shift in the timeline of slavery and antislavery to the very long period of ongoing slaving after the so-called abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in the first decade of the 19th century. Her article shows how the politics of abolition and the logic of free trade forced Austria to confront the limitations of its legal theories of freedom and liberal understandings of self-interest. Austria's conviction that it was not implicated in the slave trade at all left it ill-equipped to handle the complexities of slavery once its involvement was exposed.

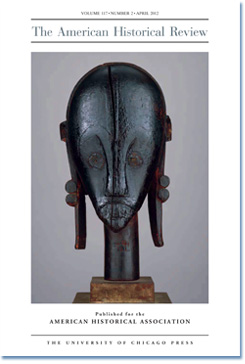

John Warne Monroe's "Surface Tensions: Empire, Parisian Modernism, and 'Authenticity' in African Sculpture, 1917–1939" looks closely at the reception of African sculpture in the interwar period in order to reassess what has been a thorny theoretical problem among cultural anthropologists and art historians: the complex and vexed capacity to appreciate so-called "traditional" objects from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas as art in the Western sense. He notes that what can seem from one angle to be a condescending emphasis on the Western connoisseur's "eye" in judging the value of exotic objects can seem from another to be a powerful means of celebrating the creative achievements of peoples and cultures previously written off in racist terms. Rather than taking sides on this question, Monroe's article builds on the insights of the new colonial history to show how the coexistence of both points of view is a legacy of the historical situation in which the idea of primitive art first emerged. This ambivalent aesthetic category, he argues, was shaped by the unique conditions of interwar France, a society distinguished both by its paradoxical attempt to function as an imperial republic and by the global influence its avant-garde exerted in cultural matters. Considered from this perspective, the emergence of the idea of primitive art suggests a new way of thinking about aesthetic modernism, its spread across geographic and cultural borders, and its relation to empire.

The June 2012 issue will contain an article on vaccine testing in interwar Algiers and an AHR Forum on "Historiographical 'Turns' in Critical Perspective."

Robert Schneider (Indiana Univ.) is the editor of the American Historical Review. He can be reached at raschnei@indiana.edu.

This imposing head, known as the “Great Biyeri,” is the work of an unidentified sculptor from the Fang people of present-day Gabon, and has become an icon of what once would have been called primitive art. The thick accumulation of palm-oil libations on its surface indicates how important it was to its original owners, who placed it atop a cylindrical bark box containing the bones of distinguished ancestors. The circumstances under which the head was taken from the former colony of French Equatorial Africa are unknown. Its first documented owner outside of Africa was the Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro, who purchased it in 1916, when he was living in Paris; by the mid-1920s, it had become the centerpiece of the art dealer Paul Guillaume's famous collection of so-called art nègre. In “Surface Tensions: Empire, Parisian Modernism, and ‘Authenticity’ in African Sculpture,” John Warne Monroe describes the context in which African objects made journeys like this one. The idea of primitive art, he argues, was a revealing and paradoxical consequence of a distinctively Parisian interaction between aesthetic modernism and colonial power. Image reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

This imposing head, known as the “Great Biyeri,” is the work of an unidentified sculptor from the Fang people of present-day Gabon, and has become an icon of what once would have been called primitive art. The thick accumulation of palm-oil libations on its surface indicates how important it was to its original owners, who placed it atop a cylindrical bark box containing the bones of distinguished ancestors. The circumstances under which the head was taken from the former colony of French Equatorial Africa are unknown. Its first documented owner outside of Africa was the Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro, who purchased it in 1916, when he was living in Paris; by the mid-1920s, it had become the centerpiece of the art dealer Paul Guillaume's famous collection of so-called art nègre. In “Surface Tensions: Empire, Parisian Modernism, and ‘Authenticity’ in African Sculpture,” John Warne Monroe describes the context in which African objects made journeys like this one. The idea of primitive art, he argues, was a revealing and paradoxical consequence of a distinctively Parisian interaction between aesthetic modernism and colonial power. Image reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

Tags: American Historical Review Scholarly Communication

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.