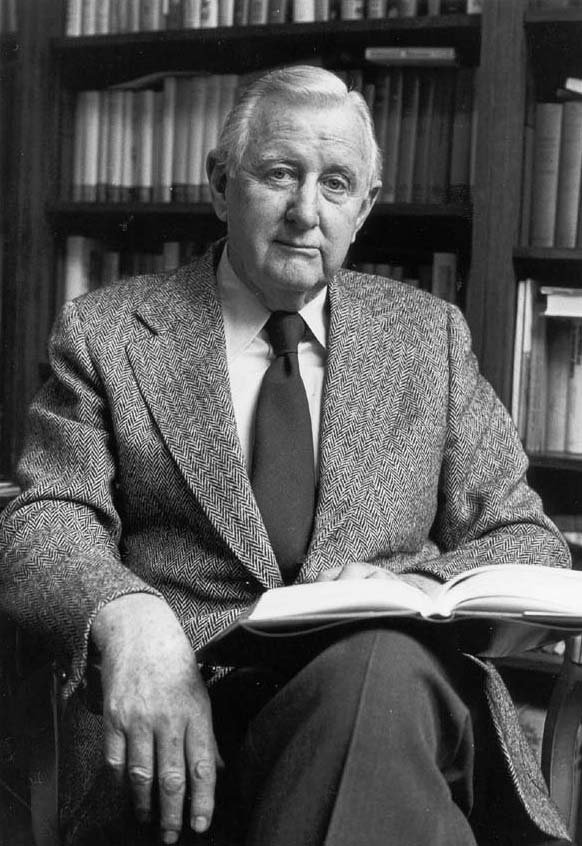

At the age of 91, C. Vann Woodward died on December 17, 1999, at his home in Hamden, Connecticut. The Sterling Professor Emeritus, Yale University, was one of the greatest historians of 20th-century America and the most influential scholar ever to interpret the history of the American South to the nation and world. His many distinctions included the presidencies of the AHA (1969: you can read his presidential address here) and the Organization of American Historians (1968–69). Recognized as a major literary figure as well, he was elected to membership in the Academy of Arts and Letters. Although his most significant works received academic recognition, in 1982 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his edited volume, Mary Chesnut's Civil War, an award long overdue. He earned these honors justly, fulfilled their responsibilities conscientiously, and wore them with gentlemanly modesty and bemused self-deprecation.

At the age of 91, C. Vann Woodward died on December 17, 1999, at his home in Hamden, Connecticut. The Sterling Professor Emeritus, Yale University, was one of the greatest historians of 20th-century America and the most influential scholar ever to interpret the history of the American South to the nation and world. His many distinctions included the presidencies of the AHA (1969: you can read his presidential address here) and the Organization of American Historians (1968–69). Recognized as a major literary figure as well, he was elected to membership in the Academy of Arts and Letters. Although his most significant works received academic recognition, in 1982 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his edited volume, Mary Chesnut's Civil War, an award long overdue. He earned these honors justly, fulfilled their responsibilities conscientiously, and wore them with gentlemanly modesty and bemused self-deprecation.

Lacking the advantage of such mentors as he himself would become for dozens of graduate students, Woodward cut his own path in the field of Southern history. Prior to the Second World War, the region's record—especially that for the years following the Civil War and Reconstruction—had languished in a backwater of Confederate nostalgia and booster exaggeration. As a young doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina in the late 1930s, he rebelled against the dreary prose of his unimpressive predecessors. In the years following World War II, almost singlehandedly Woodward demonstrated the region's complexity and its record of historical discontinuity. Harshly critical of Southern conventional wisdom, especially on matters of race and class, Woodward always regarded himself as a "rebel," though scarcely with the meaning that most white Southerners would lend that term. Before the 1940s, he risked his academic prospects by a visit to the Soviet Union and association with black intellectuals and radicals in Harlem and Chapel Hill. As a young activist who helped defend the indicted black Communist Angelo Herndon in the early 1930s, he verged on the radical side of issues himself, but later in that decade grew disillusioned with American and international Communism.

Throughout Woodward's long life, however, he retained a fervent sympathy for underdogs of whatever color or status. Raised by intellectual and Methodist parents in Arkansas, he possessed a horror of violence and consistently espoused peaceful means for effecting major changes. He abhorred tyranny and questioned ideological certitudes. Even the pre-Civil War abolitionists gave him some discomfort. Of course, still worse in his eyes were the Southern racist politicians as well as most doctrinaire ideologues of either Left or Right. In keeping with his moderate but determined position on race, Woodward assisted Thurgood Marshall and his NAACP staff regarding the historical aspects of their arguments in the Supreme Court in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case.

Although his sophisticated use of irony checked any polemical impulse, Woodward as an unabashed liberal believed that history offered moral lessons. Yet his approach was subtle, and he recommended no easy remedies. In fact, he often cast a skeptical eye on popular academic trends. His adroit balancing of message and historical verification gave much of his work a creative tension. Human destiny might be tragic he felt, but there was always hope. Only a thorough exploration of its tangled past, he affirmed in his renowned essay, "The Irony of Southern History" (1953), would free the contemporary South from its violent and oppressive heritage. Yet America, he insisted, could learn much from the Southern experience of defeat, racial and class violence and discrimination, and colonial status in a reunited, victorious Union. National complacency was ever Woodward's enemy. In the subsequent years that followed his remarks, the lesson was learned as the American armed forces struggled vainly in Vietnam. Woodward had already reminded the country that expectations of easy victories and effortless progress were the exceptions in world history, as his reading of Southern history illustrated.

Twenty-five bibliographical entries bear his name as author or editor. His essays, addresses, forewords, and reviews number in the hundreds. Yet his impact upon the profession he loved rested chiefly upon four outstanding and handsomely researched studies published between 1938 and 1955. Their significance lies in Woodward's special vision of the Southern past, in the craftsmanship of his presentation, and his lucidity, toughness, and imaginative turns of phrase. In Tom Watson, Agrarian Rebel (1938), his dissertation at the University of North Carolina, Woodward brilliantly chronicled how an idealistic young attorney boldly led the first farmer revolt against the corporation-minded Redeemer Democrats of Georgia but then turned violently racist when the Populist movement failed. In presenting a desolate South, fractured by racial and class divisions, Woodward's most magisterial work, The Origins of the New South (1951) established the period from the close of Reconstruction to the First World War as a topic of serious study for the first time. It has yet to lose its hold on the historical imagination.

Like The Origins of the New South, Reunion and Reaction, also published in 1951, offered fresh issues and annihilated longstanding myths. In this case the target was the legend of Redeemer purity in the Democratic overturning of Republican Reconstruction. Woodward sought to prove that in the disputed election of 1876 the elevation of Rutherford B. Hayes to the presidency was the result of a dubious transaction with ex-Confederate politicians, who betrayed fellow Democrats and won army removal from the South along with lucrative favors. Although Reunion and Reaction and The Origins of the New South remain monuments of scholarship, they have both undergone the usual fate of pioneering works. Subsequent historians have offered new readings of the documents.

A classic and still inspiring work, The Strange Career of Jim Crow enlarged Woodward's readership into the millions. The original set of lectures at the University of Virginia in 1955 was designed to reassure a resistant white South that Jim Crow was a relatively new arrival on the regional scene. Black disfranchisement and racial separation were in the 1890s a product of corporate fear of underclass unity and insurgency and of unfounded white dread of racial amalgamation. Liberalizing racial constraints, he implied, would right longstanding wrongs without creating new and unmanageable problems. The message was salutary as the dawn of the Civil Rights movement was breaking. Although periodically updated, The Strange Career of Jim Crow has declined in influence among historians. By no means, however, has it lost its popular influence. On the Alabama capitol steps, Martin Luther King Jr. had hailed it as "the Bible" of his reform efforts. No doubt Woodward, who marched with King at Selma in 1965, was pleased with the compliment. Yet ironically Woodward had long since rejected the scriptural faith of his forbears, although not the scriptural influences that King sensed in the historian's own work.

Half of Vann Woodward's many achievements would satisfy the ambitions of most of his admirers. The tempo of his publishing increased after he moved to Yale in 1961 from Johns Hopkins University, where he had taught since 1946. Yet, the nature of his work had already begun to change. Woodward found that reinterpretation rather than factual discovery and presentation permitted him a high degree of creativity. The literary approach was further enhanced by his association in New Haven with Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren of the English Department, both fellow Southern expatriates and old friends. New obligations and duties at Yale left little time for ransacking archives in the manner of earlier years. Moreover, Woodward often had to serve as spokesman for one or another issue before Congress or other forums. The domestic turmoil over the Vietnam War, worries regarding graduate student unionization, and various controversies about Black Nationalism or the proposed one-semester appointment of Herbert Aptheker to Davenport College at Yale were undeniable distractions.

Personal tragedies during his years at Yale also arose. The loss of his wife Glenn and their only son Peter—both to cancer—was the harshest of blows. Yet his work poured out steadily. After he retired in 1977, he did not slacken the pace but produced the superbly edited Mary Chesnut's Civil War. How did he manage so extraordinary a level of productivity over so long a period? Woodward himself never explained. Always reserved in manner, he remained to the last a private soul. Adhering to the Southern code of stoic gentility, Woodward composed Thinking Back (1986) as almost purely a study of his reactions to the reception of his writings. In that fascinating intellectual autobiography readers look in vain for the figure behind the scholarship.

In his twilight years Woodward contributed enormously to a professional issue about which he had long been concerned, the close connection between the historian and the reading public at large. A foe of pretentious jargon and scholarly obscurantism, he championed narrative history, reviewed innumerable books in widely circulated journals, and, perhaps most important, served as an exemplar of how to age gracefully—and fruitfully. As editor of the History of the United States series, he greatly enjoyed collaborating with Sheldon Meyer of Oxford University Press, while insisting on both general accessibility and high scholarship. The series included James M. McPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom (1988), which won an enormous readership. As if to demonstrate his point, three former students won Pulitzer Prizes: McPherson, William S. McFeely, and Louis Harlan.

In his later years, Woodward's interest in the work and career of his many students seemed to grow deeper. The intense and brilliant Willie Lee Rose, one of his Johns Hopkins students, was a source of special affection and pride. Her career was sadly shortened by a stroke, but Woodward's concern for her never flagged. In his composed but lively way, he liked best of all conversing with intelligent and strong-minded women. Helen Reeve, his longtime friend and stepmother of the famous actor; Susan Woodward, his accomplished daughter-in-law; Glenda Gilmore, his Yale successor in Southern history; and Penelope Laurans, associate dean at Yale, assisted his return from the Whitney Medical Center on December 16, 1999. Woodward was much relieved to regain familiar surroundings after weeks of hospitalization following heart surgery in July. He asked that his desk chair be brought from his office below to his bedroom. On the following afternoon, he sat in the chair as if, after a brief nap, he would resume the writing that had given his life its greatest meaning. This time, however, he did not awaken.

—Bertram Wyatt-Brown teaches at the University of Florida.

Tags: In Memoriam

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.