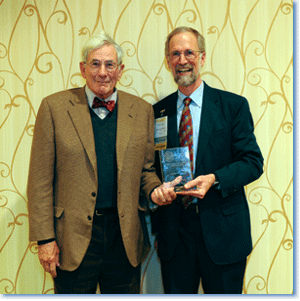

2012 Theodore Roosevelt-Woodrow Wilson Award

The American Historical Association takes great pleasure in presenting its Theodore Roosevelt-Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service to Richard Gilder—collector, philanthropist, and activist—on behalf of historical thinking in classrooms and public culture. The Roosevelt-Wilson award honors individuals outside the historical profession who have made a significant contribution to the study, teaching, and public understanding of history.

The American Historical Association takes great pleasure in presenting its Theodore Roosevelt-Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service to Richard Gilder—collector, philanthropist, and activist—on behalf of historical thinking in classrooms and public culture. The Roosevelt-Wilson award honors individuals outside the historical profession who have made a significant contribution to the study, teaching, and public understanding of history.

Richard Gilder has a long and outstanding record of enterprise and accomplishment in promoting historical studies for people of all ages. His enormous contributions to American historical consciousness include the initiation of innovative and widely influential professional development programs for high school history teachers, support for the preservation of Civil War battlefields; major purchases on behalf of historic sites, such as Monticello; establishment of major book prizes reflecting the life, times, and values of George Washington, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln; the New-York Historical Society’s annual prize for the best book on American history written for a general audience; and public exhibitions on slavery in the development of New York and on Alexander Hamilton. Gilder and his partner in philanthropy Lewis Lehrman have not only carefully collected more than sixty thousand letters, diaries, maps, pamphlets, printed books, newspapers, photographs, and ephemera that document the political, social, and economic history of the United States. They have generously donated the collection to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, which has placed it on deposit at the New-York Historical Society, where it is accessible to, teachers, students, scholars, and other researchers.

Nearly two decades ago Richard Gilder, a successful New York stockbroker, began building on his lifelong fascination with American history to create a constellation of institutions and programs that advance historical consciousness throughout our society. In 1994 he spearheaded the founding of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The Institute quickly became a center of resources and professional development opportunities for middle and high school teachers across the nation. It has had a major impact on the teaching of American history in this country, reaching thousands of teachers over the years. Today the Institute sponsors up to forty seminars each summer led by distinguished scholars in a range of fields, and has collaborated with local school districts to provide curricula and expertise for more than a dozen “history high schools” and twenty-six hundred affiliate schools across the country. The Institute also awards an annual prize competition to recognize the National History Teacher of the Year and fifty-two other state winners who teach at the K–12 level.

In 1997 Gilder deepened the impact of his philanthropy on historical scholarship by establishing the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. The first center of its kind in the world and now a model for similar research centers internationally, it supports research, scholarship, and public outreach on slavery in its myriad forms (and its legacies) throughout the modern era. In the Center’s first fourteen years Dick Gilder personally has sustained its work with more than ten million dollars.

As he puts it, “Each of these things I’ve been involved in, each one was a job that needed to be done. I could see that there’d be a big job—a job worth doing.”

In her nomination letter, Louise Mirrer of the New-York Historical Society recalls how, shortly after she arrived as provost for the City University system, Dick and Gilder Lehrman Institute President James Basker invited her to meet to discuss a project they had for several years aspired to but could not seem to achieve: an American history-themed high school on the campus of Lehman College, a CUNY school in the Bronx with an extraordinary history department. She explains,

The College administration was unenthusiastic about sharing precious space with high school students; the New York City Board of Education was unenthusiastic about creating a new school into which students had to be “tested.” Equally discouraging was the wider circle of politicians and public citizens who thought that a new, academically-challenging school in the Bronx would never work.

The project began to look hopeless. But Dick’s conviction that “If you have a good idea, it’ll build” turned out to be just right on this occasion, as on so many others. Together we managed to cut through the bureaucracy to develop what is now not only one of the top high schools in New York City, but one of the top high schools in the nation, with a student population that represents the full diversity of New York. Absent Dick, the school never would have had a chance.

David Blight, the director of the Gilder Lehrman Center at Yale, sums it up like this:

Dick Gilder, through the organizations he has helped to forge, has put faith in the very best American historians to take the very best history out as far and wide as possible—to teachers, students, and the broad public. He represents as important a connection as has ever existed between private philanthropy and public history. His resources have indeed allowed many historians to learn just how to become public historians as well as scholars.

The American Historical Association is honored to consider Richard Gilder a leader among our community of scholars. And we are grateful for his work on our behalf.