Teaching

An Assignment from Our Students: An Undergraduate View of the Historical Profession

What do 18-year-olds think of historians and our work? I should have known that was a dangerous question to ask and yet, too late to stop after the books had been ordered, the syllabus distributed, and the add/drop sessions complete, 16 first-year students and I plunged into exploring the many ways that American history lives in American society.

The students, enrolled in a first-year seminar at the University of Richmond, came connected to an array of places in the nation and the world, from a range of class and ethnic backgrounds, and had signed up for different reasons. Some of them took the class, they said, because they had always been interested in history, others because they thought it might be fun to get to know the university's president, and others, they admitted without evident embarrassment, because it was the only class that fit their schedule.

For most of these students, Touching the Past: The Purposes and Strategies of American History would be their first college history class. As a result, they provided a clear test for the questions the course explored: how does history live within our culture, beyond the college gates? What is it like to learn history in elementary and high school in the early 21st century, to grow up playing video games based on history, to be taken to local historic sites and museums, to absorb history through television and movies, to figure out where you and your family fit in the flow of space and time? What meaning might history have for digital natives, for young people for whom technology is not a disruptive force but simply a part of life?

If I wanted honest answers to these questions, I soon heard them, offered in the unguarded way that only freshmen can provide. The students confidently measured the world through what they knew, and what they knew was popular culture. That culture, often electronic in one way or another, was more pervasive and powerful than anything else they had experienced, including school. The only history books most had seen were high school textbooks, books they universally detested.

The students, not surprisingly, liked the idea that historical understanding arrives in many forms. Early on, they accepted literally and uncritically Carl Becker's "Everyman His Own Historian." They agreed with the respondents in Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen's Presence of the Past who believed that the purpose of history was to help people feel good about themselves and to respect and honor their family's heritage and traditions. They heartily endorsed James Loewen's charges that textbooks were full of lies, empty of honest truths about the past. They felt sorry for academics after surveying the best-selling history books on Amazon.com and after exploring American history on television. History, the students determined, sold only when peddled as entertainment.

My strategy of introducing students to our profession, several weeks into the course, by assigning the October 2012 issue of Perspectives on History gave me second thoughts. As I had imagined the class months earlier, this assignment had seemed clever, a parting of the curtain behind the imposing Oz of the professional enterprise. Now that I could see that the students had never fallen for the wizard in the first place, I was anxious about what they would make of our intra-professional conversation. The students read a digital copy of the print version of the publication, start to finish; the professional notes and job advertisements as well as eloquent articles by leaders in our profession.

Analyzing Perspectives as they would a historical document, they were struck, most of all, by historians' fretting: over the long odds and low salaries of our job market, over discouraging trends evident in graphs and tables, over our uncertainty about the digital world. Never having been in a profession themselves, they did not understand that such self-critical analysis is the intended work of a professional organ such as Perspectives. They saw embodied in Perspectives what they read about in Peter Novick's That Noble Dream, the fragmentation of our discipline and our loss of collective confidence. Not understanding its distribution, they came to class thinking the publication would sell poorly on newsstands in competition with the glossy American Heritagemagazines they had critiqued earlier in the semester.

It turned out to be stimulating and even funny to see our professional life through the eyes of smart young people. Their unintentionally patronizing sympathy hardly shook my faith in our work, but it did make me realize that academic historians cannot take our authority-so palpable within the disciplinary and institutional structures in which we live-for granted. It is not that today's students are, as often charged, shallow careerists, or that they hold the humanities in contempt, or are cynical or burdened with short attention spans. Instead, they simply had never been presented with the opportunity to see the work that historians do. The structures and actions of our profession, our contributions to American culture, were invisible to them, as they are to most people.

If the course had ended at midterm, quite frankly, I would have considered it a failure. My goal, after all, had not been to diminish our profession in my students' eyes, but to help them realize how history works in our culture. Fortunately, in the second half of the class the students themselves had a chance to practice history.

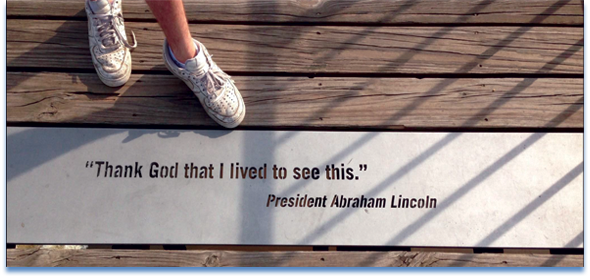

Their assignments required them to visit important sites within Richmond, observe and interview participants in the city's commemorative Civil War and Emancipation Day events, discuss primary documents from an anthology produced for discussions around the nation sponsored by the American Library Association, and read Imperiled Promise, an overview of the state of history in sites overseen by the National Park Service. Their ultimate goal was to produce a plan for the city as it commemorated the anniversaries of the end of the Civil War, the fall of Richmond as the Confederate capital, the arrival of Abraham Lincoln and United States Colored Troops, and the beginning of the long struggle for freedom and equality.

As they embarked upon this challenging work, they began to see the limitations of history they had found unproblematic earlier in the course. When they read Tony Horwitz's Confederates in the Attic, for example, they could see the dangers of every man being his own historian, the limitations of genealogical history, and the delusion that physical experience was an especially authentic path to historical understanding. When they surveyed the representation of the Civil War on the web, they could see the problems that resulted when people followed their private passions, writing just what they wanted without caring what others had documented. When they viewed popular movies about the war, they could see how selective the stories were, how much the films left out, how the formulas of even the best entertainment foreshortened history.

Forced to put history on the line in their plans for Richmond, in other words, students came to see the value and necessity of academic history, of history without a personal connection or agenda, of history disciplined and made accountable by a profession. They came to understand how a monograph written long ago could be more useful than a recent bestseller. They came to appreciate that the exhibits in museums and the words on historical markers took shape from collaborative research. They came to understand why textbooks evolved and where their teachers learned the things they taught.

The academic historian in me took quiet satisfaction from these hard-won lessons, and from the new respect students had for our profession. But any smugness proved fleeting, for, as they began to put their understanding of history into action the students argued that historians were wasting opportunities all around us. As they presented their plans for the anniversaries of the Civil War's end and of emancipation, they instinctively and insistently invoked the power of social media. We need to engage people where they are, the students told me and each other in their Prezi presentations, we must employ the tools people use every day to build communities of understanding in real time.

The students, in other words, had developed respect for the work and values of academic historians but they urged us to expand our definition of scholarship so that it would flourish in the new world of social media. The students saw current scholarly publishing as a sort of underground press, full of treasures but hidden away. They felt certain that the public that would be interested in what scholars were writing if they could just see it. They wanted to put scholarship to work in the world, to make it a living presence. Certain that social media would be essential to that presence, they suggested strategies ranging from a series of brief comic videos to contests among high school students from across the country who would use primary sources to construct a historically accurate identity for an online character. They presented their plans with great energy and enthusiasm, certain that they were connecting the best of academic history's traditions with unprecedented opportunities.

At the end of the class, as we reflected on our work together, the students encouraged me to use Perspectives, whose work they now understood, to encourage my fellow historians to be bolder in our aspirations for our work. Our profession possesses both intrinsic value and latent power, they told me. We have new ways to tell our stories to more people more memorably, to strengthen our profession without abandoning its hard-won accomplishments, to make our work more visible. I told them I would be glad to take on that assignment.

-Edward L. Ayers is president and professor of history at the University of Richmond.

Tags: Resources for Faculty Resources for History Departments Teaching Resources and Strategies

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.