News

International Congress Brings Historians from around the World to Sydney

Some 1,400 historians from around the world gathered in Australia for the 20th meeting of the International Congress of Historical Sciences (usually referred to by its French acronym, CISH), held July 3–9, 2005, in Sydney. This was the first time in the 100-year history of the congress—which convenes once every five years—has met in a venue other than Europe or North America. Although in consequence attendance fell by about a quarter from the figures for the 2000 meeting in Oslo, Norway, those who made the journey had a stimulating experience, feasting on a rich array of topics from a wide range of perspectives.

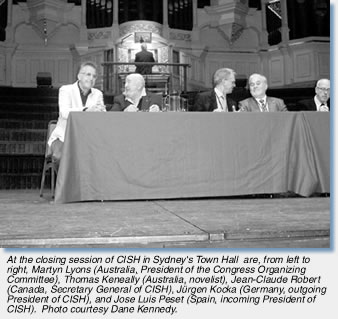

The Australian hosts of the congress took the opportunity to showcase their country, with its stunning natural beauty, unique cultural heritage, and lively intellectual environment. The University of New South Wales served as the principal venue for the conference, with many of the delegates staying at the headquarters hotel in nearby Coogee Beach, offering a vista of white sands and blue waters. The opening ceremony included a traditional greeting by local Aboriginal leaders, complete with didgeridoo, and an impressive speech by Robert (Bob) Carr, then premier of New South Wales (he retired from office several weeks later), on the contested nature of historical knowledge and its civic uses. All registered participants in the congress received gratis copies of a newly published volume of essays summarizing recent debates in Australian history, co-edited by the chair of the local organizing committee, Martyn Lyons. A scintillating keynote lecture by New Zealand’s distinguished historical anthropologist, Anne Salmond, placed Australia in the broader context of Pacific history. The highlight of the closing ceremony, held in the Victorian grandeur of Sydney’s Town Hall, was an address by Thomas Keneally, the Australian novelist and author of Schindler’s List and other works of historical fiction, who spoke in a vigorous and illuminating fashion about how his aims compare to those of the professional historian.

The Australian hosts of the congress took the opportunity to showcase their country, with its stunning natural beauty, unique cultural heritage, and lively intellectual environment. The University of New South Wales served as the principal venue for the conference, with many of the delegates staying at the headquarters hotel in nearby Coogee Beach, offering a vista of white sands and blue waters. The opening ceremony included a traditional greeting by local Aboriginal leaders, complete with didgeridoo, and an impressive speech by Robert (Bob) Carr, then premier of New South Wales (he retired from office several weeks later), on the contested nature of historical knowledge and its civic uses. All registered participants in the congress received gratis copies of a newly published volume of essays summarizing recent debates in Australian history, co-edited by the chair of the local organizing committee, Martyn Lyons. A scintillating keynote lecture by New Zealand’s distinguished historical anthropologist, Anne Salmond, placed Australia in the broader context of Pacific history. The highlight of the closing ceremony, held in the Victorian grandeur of Sydney’s Town Hall, was an address by Thomas Keneally, the Australian novelist and author of Schindler’s List and other works of historical fiction, who spoke in a vigorous and illuminating fashion about how his aims compare to those of the professional historian.

With more than 50 congress sessions and countless affiliate panels to choose from, there was something to appeal to most historians. As might be expected from a gathering designed to instigate a dialogue among scholars from different countries, the meeting stressed themes and topics that transcended national and regional boundaries, moving across them to matters of transnational or global scope and significance. It also confronted issues of relevance to our contemporary condition, demonstrating once again that the perspectives and insights offered by historians are indispensable in making sense of problems too often conceived in purely presentist terms.

Appropriately enough, the first of the congress’s major themes was devoted to "Humankind and Nature in History," a grandly ambitious topic that received a full day of richly varied treatment. Historians from Australia, Austria, Canada, India, and various other countries grappled with the issues posed by human interaction with the environment, ranging from the effects of natural disasters on human communities to the transformations that human intervention has wrought on the natural world. One of the main issues that arose from the proceedings was whether environmental history was better framed in terms of a clash between humans and nature or in terms of the human experience as an integral part of nature.

Another major theme was "War, Peace, Society and International Order in History," which included panels on theories of just war, changing conceptions of peace, and the experiences of women in war. Among the many timely features of this set of sessions was the reminder it offered that terrorism has to be understood as a highly contested category in the debate about organized violence. One panelist traced a shift in attitudes toward partisans in the two world wars: while both sides in the first war viewed partisan violence against occupying forces as illegitimate (and hence a form of terror), the allies came to view partisan forces in Nazi-occupied Europe as national heroes. A similar divergence of opinion was noted with respect to the violence that accompanied opposition to colonial regimes and other forms of resistance. The issue of terrorism was the central theme of another session, which examined its role in the modern histories of France, Ireland, and Russia. Here a distinction was drawn between terror, which was associated with the violence perpetrated by states such as revolutionary France and Stalinist Russia against its own subjects, and terrorism, which is more commonly applied to groups like the IRA and Chechen rebels that engage in violent resistance to ruling states.

Another panel took up the related subject of human rights. Participants traced its development in various national and international contexts, pointing to the tensions between its universalist claims and particularist interests, especially those arising out of wars and the political agendas of states. One panelist observed that human rights often have been circumscribed by the question of who qualifies as human, which was susceptible to answers that excluded certain peoples on the basis of race or other categories of difference. The session chair made a related point: how we address the issue of human rights is contingent on whether we place stress on "human" or on "rights." A practical demonstration of the relevance of this panel’s debates came in the session "Collision of Cultures and Identities," which focused on the clash between settlers and indigenous peoples—a subject that understandably generated particular interest from Australians and Americans in the audience.

Still another broad theme that received extensive treatment in the congress was the origins and development of globalization as an economic phenomenon. Participants dealt with issues of definition, chronology, space, and other categories of analysis. Although little in the way of consensus was reached on the subject, the session was stimulating both for its analytical rigor and for the range of topics it addressed—among them the promise and problems offered by commodity studies and the striking shifts that have occurred in world migration over the past hundred years. Questions about globalization also figured prominently in the panels, "Sugar Cane Expansion on Five Continents" and "Empires in the Near East and the Mediterranean Area," the latter raising the question whether these empires were the progenitors of what we now call globalization.

The final bracket of congress sessions included a roundtable on the status of history as a discipline, cosponsored by UNESCO. Distinguished historians from Germany, Poland, Barbados, Senegal, Syria, China, and France reflected on the profession in their countries. Their comments were fascinating both for the similarities and the differences in their perspectives. One of the most eloquent speakers was the Senegalese historian Ibrahima Thioub, who mixed wry humor and moral gravity in his remarks on the value of historical knowledge. He observed that the historian is like the driver of a car: he must always keep an eye on a rear-view mirror, but must keep in mind that he is sure to have an accident if he spends all his time gazing backward. It was an apt reminder that the historian’s interest in the past cannot be divorced from the concerns of the present.

It was a privilege for me to attend the Sydney meeting as the delegate for the AHA, one of 54 national organizations affiliated with CISH. A strong contingent of American historians participated in the congress, playing a prominent and intellectually vibrant role in its proceedings. For those of you who missed the meeting, a CD of the papers can be purchased through the conference web site, www.cishsydney2005.org. Your next opportunity to take part in the congress will come in the summer of 2010, when it will meet in Amsterdam.

—Dane Kennedy, the Elmer Louis Kayser Professor of History and International Affairs at George Washington University, is chair of the AHA’s Committee on International Historical Activities.

Tags: History News

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.