Members will have received (or will shortly get) their October issue of the American Historical Review, which contains two articles, a forum, seven featured reviews and our normal extensive book review section. The issue is also online.

Members will have received (or will shortly get) their October issue of the American Historical Review, which contains two articles, a forum, seven featured reviews and our normal extensive book review section. The issue is also online.

The first article in the issue attempts to explain Puritan “discipline” in 17th-century New England; the second examines the role of Britain in the struggle against slavery in the U.S. in the 18th and 19th centuries. The forum brings four historians together for an assessment of “The General Crisis of the 17th Century,” one of the great controversies in the field of early modern history.

In “Puritan Godly Discipline in Comparative Perspective: Legal Pluralism and the Sources of 'Intensity',” Richard J. Ross (Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), a professor of law and history,* offers an explanation for New England Puritans’ well-known drive for moral righteousness and a more fully Christianized society.* His approach is comparative, placing the Puritans in the early modern context of other post-Reformation attempts at godly discipline and confession-building, and drawing contrasts between them and other New World settlements, especially in terms of their legal systems. Indeed, he demonstrates that evidence from the New World can contribute to debates among scholars of the “confessional age” by demonstrating the importance of legal history in understanding the level of godly discipline.

In “‘As a Nation, the English Are Our Friends’: The Emergence of African American Politics in the British Atlantic, 1772–1861,” Van Gosse (Franklin and Marshall Coll.) argues that black Americans first gained significant political leverage not within the United States, but rather around it, in the extended arc of the British Empire. Among other things, he documents the impact of the Anglo-African American connection on domestic political discourse in the United States itself, ranging from a virulent southern Anglophobia regarding “New England and Old England” to African Americans’ constant evocation of the “British Lion” as their protector from the “American Eagle.” As with other recent scholarship, his article challenges the national-historical narrative of American democracy, pointing out how compromised that story was before the Civil War, especially if one looks at U.S. politics from the outside—as African Americans emphatically did.

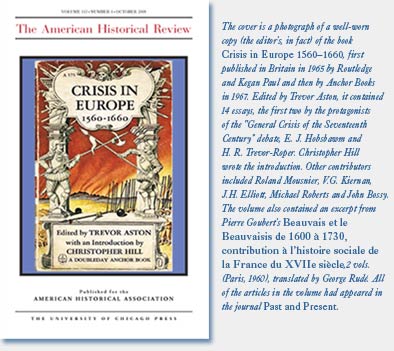

The AHR Forum, “The General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century Revisited,” takes a look at one of the great historical controversies of the post-WWII era. Initiated by Eric Hobsbawm in two articles published in 1954, the debate continued with a stream of interesting and provocative research and writing until the 1980s. In “Crisis, Chronology, and the Shape of European Social History,” Jonathan S. Dewald (SUNY, Buffalo) surveys the historiography of the “crisis” controversy during that period. He focuses on two especially influential traditions of historical writing, one deriving from Anglo-American social science and associated with the journal Past and Present, the other linked to the French Annales school. In the second article in the Forum, “Climate and Catastrophe: The Global Crisis of the Seventeenth Century Reconsidered,” Geoffrey Parker (Ohio State Univ.) offers new ways of looking at, and perhaps reviving, the concept of “crisis” for the 17th century. His perspective is global, not merely European or Western. In seeking to explain the multiple disasters that marked the period, Parker turns to environmental factors and in particular evidence of global cooling. He suggests that this “Little Ice Age” furnishes links between climate change and global catastrophe.

These articles are followed by two comments. In the first, “Locating Linkages or Painting Bulls’ Eyes around Bullet Holes: An East Asian Perspective on the Seventeenth-Century Crisis,” Michael Marmé (Fordham Univ.) considers the relevance of a 17th-century general crisis to our understanding of East Asian History. Agreeing that places far apart faced a common (climate-driven) crisis, he reminds us that the societies experiencing that crisis differed dramatically, and hence their responses differed dramatically as well. The second comment is offered by J. B. Shank (Univ. of Minnesota). In “Crisis: A Useful Category of Post Social Scientific Historical Analysis?” Shank examines historians’ use of this term, explaining how it was first associated with medical science and social scientific approaches to history. It was this association which determined our understanding of the concept in the “general crisis of the seventeenth century,” an understanding that Shank would like to see reassessed.

Looking ahead, the December 2008 issue of the AHR will also offer a look back at another important historical contribution: Joan W. Scott’s “Gender: A Useful Category for Historical Analysis,” which appeared in the AHR in 1986. Six historians, with different regional and historical perspectives, will reassess the impact and continuing relevance of this article, with Scott (Rutgers Univ. at New Brunswick, and Inst. for Advanced Study, Princeton) offering her own response to the essays.

—Robert A. Schneider (Indiana Univ.) is the editor of the AHR.

*The text in this online version has been revised to correct the inadvertent omission of "and history" from the print version.

Tags: AHA Activities Scholarly Communication

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.