Some of our readers will no doubt disagree with the interpretive perspective presented here. My goal in this essay is to highlight one aspect of historians’ role as mediators between the past and the present. Historic sites, for example, offer marvelous opportunities to challenge public culture to confront the implications as well as the meaning of history.

Some of our readers will no doubt disagree with the interpretive perspective presented here. My goal in this essay is to highlight one aspect of historians’ role as mediators between the past and the present. Historic sites, for example, offer marvelous opportunities to challenge public culture to confront the implications as well as the meaning of history.

February 12, 2011

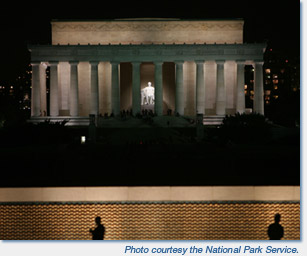

This afternoon my wife and I visited the Lincoln Memorial. It seemed like the right thing to do on Lincoln’s birthday, to two people still relatively new to Washington. Despite the winter chill (at least by Washington standards), a steady stream of visitors climbed the steep stairs. At the top one could see approximately a dozen wreaths, placed by entities ranging from a local church, to various veterans’ organizations, the Gold Star Mothers, the government of the District of Columbia, and the President of the United States. Judging from the overheard whispers (“it’s his birthday”), I’m guessing that some tourists knew about the holiday only because of the wreaths; after all, it’s not a holiday anymore—one less reminder of the central role of slavery and emancipation in American history.

Actually it’s far more complicated than that. I grew up with two holidays: Lincoln’s Birthday and Washington’s Birthday. In 1968, Congress authorized the “federal holiday on Mondays” structure that provided Americans with three-day weekends, but ripped commemorations from their temporal moorings. Because everywhere I’ve lived since the new system began in 1971 (four states plus D.C.) had references to “Presidents’ Day” splashed across the newspapers, I have always just assumed that’s what we celebrate on the third Monday in February. Not so. Congress did not want to require Americans to celebrate presidents they don’t like, so the official holiday remained Washington’s Birthday—even though the third Monday in February cannot ever fall on February 22. Basically every state calls it whatever they want. Virginia, which seems habitually inclined to go its own way on historical issues, celebrates “George Washington Day.” Alabama adds Thomas Jefferson to the commemoration, although his birthday does not arrive until April.

So what happened to Lincoln? Except in Connecticut, Missouri, and Illinois, he has disappeared from the official calendar. Given the ubiquity of the Lincoln Bicentennial, not to mention the Civil War Sesquicentennial, we don’t need to worry about honest Abe’s visibility, especially in the short run. I’m more concerned with what we learn from a site visited as heavily as the Lincoln Memorial.

As I read Lincoln’s second inaugural address in the north wing of the Memorial, I was reminded once again of how his perspective had changed in the 16 months since the Gettysburg Address (inscribed on the opposite wall). By March of 1865 Lincoln was prepared to state publicly that the war was about slavery. “All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war.” Our children are still reading textbooks that refuse to accept this crucial insight. But now, as we move into the five years of commemorating the war, we need to get it right.

Lincoln was also prepared to warn Americans that if we couldn’t settle this problem, the wrath of God would know few bounds:

“Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

This passage immediately precedes the more often quoted “With malice toward none; with charity for all,” the healing gesture that points toward reconciliation. To a considerable extent, however, such reconciliation took place on the backs of black Southerners, for whom the war recommenced after Reconstruction, in the form of terrorism. Historians have documented that war extensively; yet it remains neither well known nor well understood in public culture. As we move into five years of Civil War commemoration we need to remember these two very basic facts: the war was fundamentally about slavery; and the war continued in the form of the physical and emotional terror that was lynching, everyday intimidation, and Jim Crow.

It is important to teach this history. And it is also important to teach about hope and change—about how emancipation did make a difference. And how, after a long struggle and many martyrs, the federal government compelled an end to the Jim Crow regime and all it implied. Lincoln’s Memorial, and his birthday, should remind us of both our sins and “the better angels of our nature.”

The Lord continues to judge.

James Grossman is the executive director of the American Historical Association.

Tags: From the Executive Director AHA Leadership North America Public History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.