From the President

In Praise of the Variegated Life

.jpg) The monthly presidential messages in Perspectives on History have always struck me as pastoral in tone and function: designed to speak to the flock of practicing historians as a collectivity, to address our common way of life as well as our shared problems and pursuits, to counsel us, to cheer us on, to reinforce our devotion. When I accepted the nomination for the presidency of the AHA, I wondered if I had the vocation, the requisite "pastoral personality," to pull off that aspect of the job. So it is perhaps not accidental that, for my first presidential column, in which I naturally wanted to address the Big Issues facing our discipline today, my thoughts turned, despite my ordinarily secular outlook, to things clerical. Two things clerical, to be precise. The first was the rhapsodic and wildly neologistic Victorian Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose poems I first encountered in high school. The second was a flyer for visitors that I picked up as a tourist in a fairly obscure Breton cathedral last summer.

The monthly presidential messages in Perspectives on History have always struck me as pastoral in tone and function: designed to speak to the flock of practicing historians as a collectivity, to address our common way of life as well as our shared problems and pursuits, to counsel us, to cheer us on, to reinforce our devotion. When I accepted the nomination for the presidency of the AHA, I wondered if I had the vocation, the requisite "pastoral personality," to pull off that aspect of the job. So it is perhaps not accidental that, for my first presidential column, in which I naturally wanted to address the Big Issues facing our discipline today, my thoughts turned, despite my ordinarily secular outlook, to things clerical. Two things clerical, to be precise. The first was the rhapsodic and wildly neologistic Victorian Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose poems I first encountered in high school. The second was a flyer for visitors that I picked up as a tourist in a fairly obscure Breton cathedral last summer.

It was Hopkins’s poem “Pied Beauty” that came to mind; it begins “Glory be to God for dappled things / For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow.” The poem goes on to extol the man-made landscape as well as the natural one (“And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim”) and to single out for special praise “All things counter, original, spare, strange; / Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?).” The relevance of this oddly worded hymn to us historians and to our professional organization is not, I think, terribly hard to grasp. It is the conviction that we share with Hopkins about the inexhaustible interestingness of the world, both natural and human, that fuels our historical curiosity. That conviction keeps us going through the daily slog. It enables us to carry out protracted and painstaking research labors for the sake of achieving some rational understanding of the past in order to orient ourselves in the present and to think intelligently about the future. In addition to speaking to our most basic motivations as students of the past, Hopkins’s “pied beauty” also refers to the historical profession as we have been deliberately constituting it in recent decades: one that includes the widest diversity of practitioners and of subjects treated, that encompasses, in addition to the military and diplomatic matters that readily satisfied our distant professional predecessors, “all things counter, original, spare, strange.”

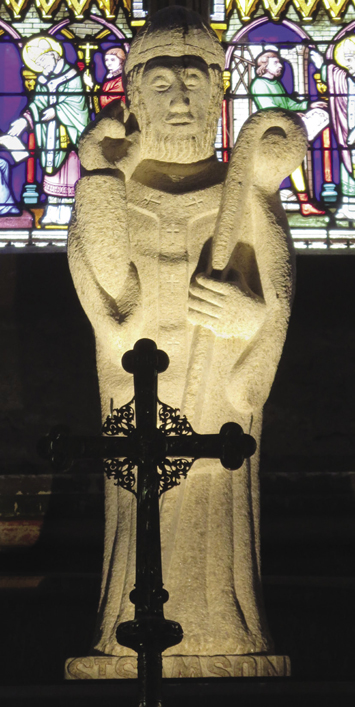

From Hopkins’s quirky and inspiring lyricism, I turn to my second example. The Cathedral of Saint Samson in the little town of Dol-de-Bretagne is dedicated to a sixth-century hermit regarded as one of the founders of Christianity in Brittany, a region in France famous for its Catholic piety. A stone sculpture of Samson depicts a man with the solidity of a pillar, long-suffering, patient, and firm. The majestic building, parts of it dating from the 12th century, had surprisingly few visitors on the afternoon in late August when my husband and I stopped by. Perhaps it is simply overshadowed by Mont Saint-Michel, the mega-attraction just across the bay, and has never made it onto the general tourist circuit. In any case, a table at the front of the church offered a flyer to guide the visitor around the imposing building. The first recommended stop was the crucifix in the nave. “The cross,” read the flyer (and I translate from the French), “is the ‘logo’ par excellence of Christians. It recalls that Jesus Christ died and rose from the dead for all mankind.”

From Hopkins’s quirky and inspiring lyricism, I turn to my second example. The Cathedral of Saint Samson in the little town of Dol-de-Bretagne is dedicated to a sixth-century hermit regarded as one of the founders of Christianity in Brittany, a region in France famous for its Catholic piety. A stone sculpture of Samson depicts a man with the solidity of a pillar, long-suffering, patient, and firm. The majestic building, parts of it dating from the 12th century, had surprisingly few visitors on the afternoon in late August when my husband and I stopped by. Perhaps it is simply overshadowed by Mont Saint-Michel, the mega-attraction just across the bay, and has never made it onto the general tourist circuit. In any case, a table at the front of the church offered a flyer to guide the visitor around the imposing building. The first recommended stop was the crucifix in the nave. “The cross,” read the flyer (and I translate from the French), “is the ‘logo’ par excellence of Christians. It recalls that Jesus Christ died and rose from the dead for all mankind.”

What are we to make of the crucifix as a “logo”? Apparently the keepers of the cathedral regard today’s international tourists as a largely nonreligious bunch who, finding themselves in Brittany, require the most elementary instruction in Christian iconography to appreciate their surroundings. They choose the word “logo” to make contact with these people, to explain the otherwise arcane concept of symbolism. After all, the tourists are sporting Nike sneakers with their swoosh, Lacoste polo shirts with their little alligators, Louis Vuitton bags (real or faux) with their interlocked initials. To the local Bretons who care about the maintenance and survival of their medieval cathedral, the language of “logo” apparently seems the surest way to reach these latter-day pilgrims. Now the keepers of the cathedral may in fact vastly exaggerate the religious ignorance of their visitors: I rather suspect that they do. But the key point for my purposes is that, feeling beleaguered in a contemporary world that threatens to pass them by and casting about for shared ground with their public, they hit upon the language of the marketplace. The marketplace, they seem to say, is our common denominator as human beings in the 21st century, maybe the only reliable one.

And they are, of course, hardly alone in thinking so. Their effort to reach out to the gaggle of tourists who stumble into the sanctuary of the venerable Samson is, rather, symptomatic of the prevalent assumptions of our era. Other voices testify to those same prevalent assumptions not by tacitly accepting them but by identifying them as dissonant and pushing back against them. Last spring, for example, a Viennese cardinal felt obliged to explain the lengthy deliberative process that led to the election of Pope Francis by pointing out the very particular—and unusual—criteria involved. The role in question, he told the press, “was not ‘the chief executive of a multinational company, but the spiritual head of a community of believers.’”1 On a different register but speaking to the same point were the testy comments of a veteran of the New York fashion industry, the longtime editor of Women’s Wear Daily. Deeply committed to the idea of fashion as a creative pursuit (“the only discipline where there is no creative down time,” she calls it), she “scoff[ed] at the concept of ‘self-branding’” rife among today’s fashion designers, regarding it as a demeaning category mistake. “‘When I started in this business,’” she observed, “‘Coca-Cola, Cherokee and Clorox were brands. Fashion houses were houses, newspapers were newspapers.’”2

I’ve brought the Hopkins poem together with these ephemeral texts to propose a concept that I’ll call “variegation.” I choose that word deliberately to distinguish it from the much more familiar “diversity.” In recent decades, the American historical profession has taken large strides toward embracing diversity as a principle and a practice. But we are now powerfully threatened with sameness from a new direction: an ambient and insidious cultural pressure to recognize the hegemony of the economy over our lives and, accordingly, to translate all of our activities into economic terms.

Variegation, a rallying cry that would have pleased Hopkins, resists that pressure. I would define it as the capacity to live a life in which multiple value systems hold sway in productive tension with one another. More concretely, it is the rejection of the idea that economic utility is the only thing that really counts, that our lives would be better if we acknowledged that they were lived only in marketplaces, and that we should thus reconfigure institutions built to other standards so that their presumably true character as market actors is made palpable. By extension, it is the rejection of the idea that an educational institution, whether privately or publicly run, is fundamentally a business with customers and that its primary goal is to ready human capital for successful entrance into the job market.

Certainly the economic precariousness of our own era has painfully accentuated the role of the economy in our lives. As historians we are daily faced with the dwindling availability of tenure-track jobs in higher education and the increasing numbers of historians working without job security or adequate wages as adjuncts. Rightly or wrongly, many of us are haunted by the specter that MOOCs may one day doom flesh-and-blood college teachers to technological unemployment. It is important that the discipline bend, that it adapt its ways, to ensure its survival in such an environment. The AHA has committed itself to this strategy.

But as we historians know better than anyone, no historical environment lasts forever. In the process of strategic adaptation, we must be careful not to bend too far nor give ourselves over too completely to our efforts to induce the market to smile on us. A deliberate balancing act is required, one for which the Saint Samson flyer is not our ideal role model. We must remember what brought us into this profession: intellectual curiosity; a belief that the kind of understanding of the human situation achieved through rigorous historical investigation is indispensable even if not especially marketable; a conviction that familiarity with historical change will prevent us from ever accepting the present as inevitable but will keep us attuned to the possibility of other futures. We must insist, unapologetically, that these values coexist with—and contest—market values in a democratic society. Our vocation as historians should, in other words, include the defense of variegation—of the irreducible complexity and inexhaustible interestingness of the world of which Gerard Manley Hopkins sang.

—Jan Goldstein is the president of the AHA.

Notes

1. Rachel Donadio, “Cardinals Pick Bergoglio, Who Will Be Pope Francis,” New York Times, March 13, 2013.

2. Ruth La Ferla, "The Seat of Power," New York Times, Thursday Styles, April 4, 2013, p. E9.

Tags: History News Profession Resources for Early Career Resources for Faculty Resources for Graduate Students

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.