Noteworthy

Historians Face the E-Future

Findings from the Carnegie Scholar Survey on Computer Mediated Learning Environments

A summary version of the report can be found here.

Computers and their digital environments continue to enter the history profession although their benefits are not clear. Even the trailblazers in historical computing debate the long-term effects of their innovations. The problem of long-term evaluation is compounded by the great variety of uses, such as statistical analyses, e-mail, and on-line databases. We also lack essential information regarding the effect of computers on teaching and learning. After almost a decade of web browsing and more than thirty years of computing, historians need to address what we are doing in this medium and what we ought to be doing.

In an effort to begin such an assignment, Orville Vernon Burton, under the auspices of the Carnegie Academy for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (CASTL), in the spring of 2001 conducted a survey of historians who use CLEs. For the purpose of this study, computer-mediated learning environment (CLE) means any computer site, program, tool, or presentation employed in the distribution or creation of historical information and resources. The intent of this targeted, non-random Carnegie Scholar Survey is to define what issues regarding CLEs are important to historians.

The results from this survey highlight some of the key concerns and issues that historians face when they create or use CLEs in research and teaching. The survey was not random, but sought responses from the leaders in historical computing. We reason a constructive dialogue should begin with those most involved. While future efforts should consider a broader canvassing of the profession, we were pleased to find that the 81 historians who responded are, as one scholar noted, "not wild-eyed enthusiasts; they are seriously critical and have mixed feelings." There is much careful consideration regarding the costs and benefits of historical computing, but as we toil with the issues, we also struggle integrating this concern among our professional priorities. We feel confident that issues addressed in this survey are of vital and sustaining interest to professional historians. Among the many points of inquiry that arose in the course of respondents' answers, these five seem essential:

- What real difference have CLEs made, and will continue to make, on the nature and practice of history?

- How do we balance the desire of many historians to use CLEs in their teaching with their deep pessimism about the abilities of students to use them in a responsible and intellectually rigorous way?

- What impact will CLEs have on the library skills and research methods of scholars and students?

- How do we teach our students to separate the wheat from the chaff on the Web?

- What is the place of CLEs in teaching and (particularly) research in the reward and incentive structure of the academy?

Methodology

In September and October 2000 the Carnegie Scholar Survey team held planning meetings to brainstorm the issues and compose a first draft of survey questions. We then asked survey specialists for their input. We sent our draft out to educational technology specialists and to selected leaders in the field of Instructional Technologies and History for comment and revision. At the same time as drafting the survey itself, we compiled a non-random list of leaders in the field.

On April 5, 2001 we sent the survey via email to the first batch of recipients, forty-five individuals. On April 17 we sent it out again to those who had not yet responded. We did this a third time on May 17. This first group had a response rate of 51.1%. On May 22, 2001 we targeted a second group of recipients. This group of thirty-five individuals generated a response rate of 22.9%. (The onset of summer vacations reduced our potential response rate.) In sum we polled eighty-one individuals, of whom thirty-one responded by June 4, 2001, creating an overall response rate of 38.3%. In addition to completed surveys, we also received sundry e-mails from recipients expressing interest in the project and regret that they did not have time to complete the survey in a timely fashion.

Conclusions

1. What real difference have CLEs made, and will continue to make, on the nature and practice of history?

There is a deep divide among the respondents, between those who believe CLEs have and will transform the nature and practice of history, and those who believe CLEs offer improved access to materials, but otherwise make little difference. As one leading light of the incipient on-line revolution put it, "the possibilities are limited only by imagination, resources, and time. Any other relationship is possible, since CLEs are remarkably flexible tools." Another respondent noted that "our job as history teachers will be less to serve as lecture-based information conveyors (though that will still be useful) and more as 'tour guides,' 'pathfinders,' and expert evaluators of an otherwise overwhelming amount of information." These responses point to a potentially fundamental shift in the way we teach and (more problematically) the way we research and convey our findings to a wider audience: "CLEs raise significant issues of authority, research methodology, and pedagogy. Some types of college experience (and maybe even some types of colleges) may no longer be needed, at least in the forms familiar over the last fifty years. Historians will have to work even harder to sell the notion of history as a special paid profession to the larger world. The best institutions and the best historians will adapt."

On the other hand, many respondents observed the tendency to employ CLEs in a fashion perpetuating current practices rather than opening new ways to practice or teach history.

Some scholars sounded warning notes about the dangers of over-reliance on CLEs. For one respondent the fear was that "Students also are much more likely to be willing to develop their analytic skills in relation to visually exciting data rather than the written word. It is also hard to get them to be properly skeptical of some of the junk they obtain on-line."

In many ways, this is the same dichotomy that surfaces each time a "revolutionary" technology emerges (from the overhead projector to the personal computer to the Internet). While not providing answers to this dilemma, this survey shows little doubt that CLEs and the Internet's relationship with History are here to stay.

2. How do we balance the desire of many historians to use CLEs in their teaching with their deep pessimism about the abilities of students to use them in a responsible and intellectually rigorous way?

There is a fundamental conflict between the desire of the respondents to adopt CLEs in their teaching and a deep pessimism about the abilities of students to use them. On the one hand, respondents recognized the promise of CLEs in instruction, both in their familiarity to students and in their democratizing potential. As one scholar put it, "This generation of students is a digital generation and they will naturally expect learning to be visual and fast, and conducive to their culture that celebrates transcience over understanding." Another noted, "I think it inevitable that increased access to knowledge will help democratize the academy in a way comparable to the effects of the GI Bill in the post WWII era." Strong words indeed.

The downside of this is the facile and uncritical way that many respondents see current undergraduates engaging CLEs: "I am constantly amazed at how few of these members, supposedly, of the first 'wired' generation, use computers in any really meaningful way. . . . Many can barely use word-processing software-I really do believe that they lose files at the last minute, etc, because they barely know how to use the computer at all. They certainly don't have a clue what to do when their printer turns on them, the system crashes." Another pointed to our need as a profession to eradicate the student mindset that "if it is not on the web, it does not exist. We need to integrate information literacy into undergraduate teaching at a much faster pace." Our students use the Internet as a primary resource, and if we do not we risk becoming increasingly antiquated, and perhaps even irrelevant as a profession of educators and public intellectuals.

Speed and ease of use, which are considered positive CLE contributions when the respondents refer to their personal use, are negative features when students use CLEs as the shortest distance to completing an assignment. This paradox sits at the heart of CLE use: if so many scholars disparage the ability of their students to use CLEs, and indeed doubt their ability ever to use them effectively, then it appears CLE integration in teaching has little value. Nevertheless, and perhaps contrary to the force of their specific concerns, most respondents believe there is a need to continue this process. None of the respondents suggested how historians might address this conflict.

3. What impact will CLEs have on the library skills and research methods of scholars and students?

Yet again the responses to the Carnegie Scholar Survey saw a mixed future on this topic. For some, the possibilities are great, "the ability to do so many things so rapidly and to store data and articles on servers cheaply, should help free historical scholarship from the criticism of being 'unmarketable.'" Respondents remarked that CLEs provide access to historical materials which is particularly important to faculty teaching at non-research universities and colleges. Some also noted CLEs promoted better communication among scholars. In a cautionary note, one respondent wrote, "e-mail and listservs have made us simultaneously more interdisciplinary and more isolated in self-selected sub-communities. These latter make it harder to have serendipitous encounters with people who have different interests and who think differently." And of course, many respondents pointed to the pervasive and "massive intellectual property theft (e.g., plagiarism) that occurs primarily on an undergraduate level."

Overall, respondents concluded that increased access to material on-line has had a dramatically negative impact on the reliance on traditional print sources for research and teaching. One argued that "younger students expect to do too much of their research online and let their other library skills lie undeveloped." Another argued that "the only danger of CLEs, as I see it, is if we use them in ways which discount the critical importance of print culture for historians, and fail to train students to read conventional sources extensively and critically. CLEs should motivate students to go to libraries and even consult archival collections where possible."

4. How do we teach our students to separate the wheat from the chaff on the Web?

Many respondents expressed the concern that quality control on the web is a serious problem. This concern held true for respondents who also indicated they provided research guidelines regarding web-based CLEs for their students. Although the concern appears similar to the issue of using traditional sources effectively, the problem is greater because students have easier access to more radical opinions.

For professional historians what is interesting is not so much the web sites they identify as "authoritative," but the criteria by which they judge the "authority in content" of a particular website. Traditional ways of judging these qualities in a monograph are being transferred to the web. As one respondent noted, "My criteria would be a) author/creator's credentials and reputation, b) consultants and links, or the names that would show up in a printed book's acknowledgements, c) reliability, breadth, and carefulness with primary sources, d) quality of prose and argument." Another noted that, "although one of the major strengths of the web is easy access-for viewers and those wishing to post material, there is a huge problem with identifying reliable and helpful sites. While we need not have a Historical Web Materials czar, it would be an enormous benefit if we could have greater indexing of materials and sites. This would not only provide a reliable guide to materials that do exist, it would also suggest to people what areas most need attention."

Several others suggested that we need to pay serious attention to the effect of CLEs on our students, noting that "in a very general sense, I find that undergraduate students-whether History majors or not-tend to do exactly what we require of them and not one iota of work beyond it; however, if we assign a paper of any length, they will immediately log on to the nearest computer and will trust any web site they can find." Restricting the number of web sources often does little to change students' uncritical engagement. A respondent gauged the problem by noting it was possible to predict the search engine rank of a bibliographic entry: the higher the result on a search engine list, the more likely it would show up in the bibliography. Rather than being a problem of quality, respondents believe such problems reflect students' preference for speed over effort.

5. What is the place of CLEs in teaching and (particularly) research in the reward and incentive structure of the academy?

This is a critical question facing the academy in the twenty-first century. Have our paradigms of professional advancement and recognition advanced sufficiently to meet the needs of the Internet-ready generation of scholars? Two of the leading figures in this generation think not; for one the key is how to obtain "recognition at tenure and promotion time, most of all. The demand is there but bottled up by fears of professional suicide." For the other, "the nonsense of having colleagues who have no understanding or interest in CLE based research and teaching blocking the professional advancement of those of us who do, has to stop." Respondents questioned what the leading academic organizations, both established and emergent, can do to foster a change in the mindset of the profession?

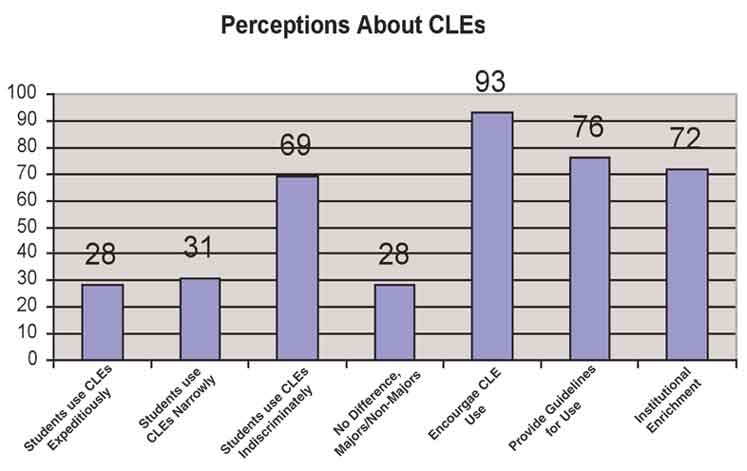

The Results In Graphic Detail

Respondents' opinions are detailed in three graphs revealing a brief demographic profile, specific perceptions about CLEs, and details of CLE use. These historians, with more than a decade of computing in both teaching and research, hold much experience, skepticism, and expectation regarding CLEs. They provide strong support for students when CLEs are involved but recognize student use and understanding often falls short of what teachers desire. They especially note a general weakness in the critical use of CLEs, suggesting students favor dispatch over quality. The other side of the equation appears somewhat brighter. Most report good institutional support and some, limited professional recognition. Despite a rising profile for CLEs in history, however, the respondents note that CLEs have yet to make much difference in the profession. Not surprisingly, respondents suggest that the low funding for CLEs matches their low professional effect.

Questions corresponding to graph depicting Profile of Respondents:

- How long have you used CLEs in your professional life? How has your use of CLEs evolved over time?

- Please rank the extent to which you employ CLEs in your professional life: choose 1-10 where 1 is e-mail alone and 10 is programming.

- From a scale of 1 to 10, could you rate the authoritativeness of history materials you have come in contact with on the World Wide Web?

- Please rank the extent to which you employ CLEs in your research: choose 1-10 where 1 is no use and 10 is fully integrated.

- Please rank the extent to which you employ CLEs in your teaching: choose 1-10 where 1 is no use and 10 is fully integrated into your lesson plans

Questions corresponding to graph depicting Perceptions of CLEs:

- What is your sense of how most of your students employ CLEs in their academic endeavors?

- Are there differences in the way that majors and non-majors employ CLEs?

- Do you encourage/discourage your students' use of Internet resources?

- If so, do you give students research guidelines for WWW use?

- Has your department/division/ college offered seminars on CLE research and / or teaching methodology?

Final Thoughts

Many among us have embraced CLEs as a primary mode of scholarship, and articles on various aspects of this discipline are a staple in the journals and newsletters of the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association, not to mention the hundreds and thousands of H-Net editors and members. Yet, this survey shows that most of the respondents wanted a better assessment of the potential benefits. They raise a wide array of questions that we have to face as a profession. What will be the overall transformative effect of CLEs on History? Who is in control of this transformation, our students or us? If it is the latter, how can we gain or share control? How do we reward colleagues who employ modes of scholarship that others might not understand or appreciate? How do we judge the quality of CLEs in comparison to more traditional and familiar forms of research and teaching? As one participant pointed out, "I think the most pressing issue is to focus on how new media are changing student learning. No one knows and almost no one is even trying to find out. If we don't figure this out pretty soon, we'll lose what little control we have over student learning!"

Ultimately, if we take away one conclusion from this survey, it should be this: CLE use is already certain; now we must determine how to invest our time and creativity into CLEs, guiding their applications in history research and teaching-respecting CLEs as a medium, and not the message.

The Authors

—Orville Vernon Burton is Professor of History and University Distinguished Teacher /Scholar at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He was selected nationwide as the 1999 U.S. Research and Doctoral University Professor of the Year (presented by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and by the Council for Advancement and Support of Education) and this year received the UIUC Graduate College Outstanding Mentor Award. He Heads the Initiative for Social Sciences and Humanities at the National Center for Supecomputing Applications. He can be reached at vburton@ncsa.uiuc.edu.

—David F. Herr is an Assistant Professor of History at St. Andrews Presbyterian College, an editor of H-South, and past project coordinator of RiverWeb. His research interests include computing in history as well as early nineteenth century Southern community, religion, and slavery. He can be reached at herrdf@sapc.edu.

—Ian Binnington is Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Eastern Illinois University. His research interests center on the symbolism and iconography of wartime Confederate nationalism. He is also the Book Review Editor for H-South. He can be reached at cfib@eiu.edu.

—Matthew Cheney is an undergraduate at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research interests include computing in history as well as race relations and the Voting Rights Act. He is also the project manager of RiverWeb and the Web Editor for H-South. He can be reached at mcheney@uiuc.edu.

Tags: Scholarly Communication

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.