Public History

Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On: Working on an Exhibit at the Folger Shakespeare Library

Research and writing can be a solitary business. And after all the work is done and the article or book is published, one sometimes wonders just how many people will actually have read it. Working on an exhibit is very different; there is a whole team working together and many, many people come to see the exhibit in the months that it open to viewing. While we do have word limits when we write articles and books, we can be quite expansive. In contrast, writing for an exhibit has to be extremely tight. Case labels have to be between 100–125 words and each item label about 50–75 words. And working on an exhibit offers unique challenges and special pleasures, as I discovered when I worked as a co-curator for an exhibit at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

Research and writing can be a solitary business. And after all the work is done and the article or book is published, one sometimes wonders just how many people will actually have read it. Working on an exhibit is very different; there is a whole team working together and many, many people come to see the exhibit in the months that it open to viewing. While we do have word limits when we write articles and books, we can be quite expansive. In contrast, writing for an exhibit has to be extremely tight. Case labels have to be between 100–125 words and each item label about 50–75 words. And working on an exhibit offers unique challenges and special pleasures, as I discovered when I worked as a co-curator for an exhibit at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

I am an early modern English cultural historian, and my recent research and writing was on the subject of dreams in 16th- and 17th-century England. I had the great good fortune to spend the academic year 2006–07 as a National Endowment for the Humanities long-term fellow at the Folger Library, one of the premier research libraries in the world in the field of Renaissance studies. The Folger has a wonderful community of scholars some of whom are readers and fellows and some of whom are on staff there. I was able to talk about my work with many fine scholars who often gave me leads to more sources.

For me the most significant find was a 1605 manuscript about dreams by the physician Richard Haydock, which he dedicated to King James I. Haydock wrote the manuscript as part of his apology to James for the fraud he perpetrated as the “sleeping preacher.” From his Oxford student days through his establishment of a medical practice in Salisbury, Haydock gave clear, intellectually engaging sermons seemingly in his sleep. James I was so fascinated to hear about the sleeping preacher that he had Haydock brought to court. While Haydock dazzled courtiers with his sermons delivered while apparently asleep, James himself was suspicious, eventually got Haydock to confess that it was a fraudulent performance. Haydock only pretended to be asleep, but was really awake when he preached. Haydock explained that he had a bad stutter and had gotten up late at night to practice preaching to see if he could speak clearly. Someone had heard him and thought he was preaching in his sleep and Haydock let them think so as he got more and more famous. Because his “sleeping” sermons had praised James, the king forgave him. Haydock returned to his practice in Salisbury and wrote his manuscript. As far as we know the one at the Folger is the only extant copy.

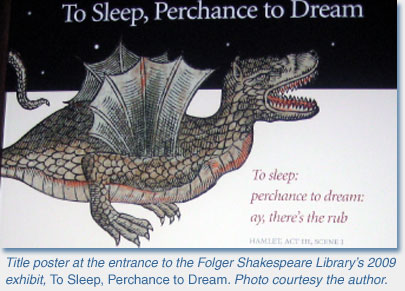

Among those I chatted with about the Haydock book and other dream stuff were Garrett Sullivan, professor of English at Penn State University whose specialty is the meaning of sleep in Renaissance literature, and Heather Wolfe, curator of manuscripts. The three of us thought it might be really interesting to do an exhibit on sleep and dreams with the Haydock manuscript as part of it. This is the genesis for the exhibit on sleep and dreams in the age of Shakespeare, with the title taken from Hamlet, “To Sleep, Perchance to Dream,” that was on display February–May 2009. Gail Kern Paster, the director of the Folger, was the one who thought of the title. That was how this exhibit started, though the ideas for it and on what we focused changed over the two years that we worked on it.

Working on an exhibit is dynamic and even unpredictable—ideas come and go, and apparently wonderful plans have to be jettisoned. Working with Garrett Sullivan, my co-curator, and me were wonderful people on staff at the Folger. Besides Heather Wolfe, our team included Steven Galbraith, curator of rare books, Karen Kettnich of the reading room staff, and coordinating it all was the exhibitions manager, first Virginia Millington, then her successor Caryn Lazzuri. J. Franklin Mowery, the head of conservation, and the rest of his staff worked with us about the items that could be exhibited in cases and making sure they were ready to be thus shown. Garland Scott and Amy Arden worked with us throughout on publicity. I was the only historian in the group—a number of the others, while knowledgeable about the history in the time of Shakespeare, were trained in literature. Working with an interdisciplinary group had many benefits, and I believe the exhibit was all the richer for our different backgrounds. But sometimes things that seemed obvious to me were not to my colleagues and vice versa. Fortunately we were able to talk it all through, and I am deeply glad that I had a co-curator not in my own field.

As we planned the exhibit one issue was that, however fascinating some books were, if they were not visually interesting or easy to read they probably were not going to end up in the exhibit. I had a lot of texts on my list that ultimately were not included. It was very important to have a line through the exhibit thematically, and so a lot of the topics for cases we originally thought of also in the end were not used, or were greatly revised. Our final decision was to begin with preparing for going to bed and five cases on sleep; a transition with cases about Haydock and James I; a case that suggested an Elizabethan bedchamber; and then five cases about dreams. Our final case was about waking up. In the sleep section the cases explored the themes of preparing for sleep, when, where, and how people slept, the significance of sleep, and how elusive sleep was for people in the Renaissance, just as it is today, and the remedies they had. The dream cases presented information about definitions of dreams, the different ways dreams were interpreted, nightmares, ways to control dream and avoid nightmares, the nature of supernatural and divine dreams, and of dreams that were concerned with politics.

The exhibit began with a large introductory panel that gave the title and some information about the exhibit. It was a gorgeous panel illustrated with a dragon. We had all fallen in love with the dragon. I had found the dragon as a hand-colored illustration in Edward Topsell’s 1608 edition of The historie of serpents. The book talked not only about the meaning of dreaming about dragons, but also offered a recipe for having pleasant dreams: to soak a dragon’s tongue in wine before drinking it. We all loved the illustration, so even though its connection to sleep and dreams was not so obvious we decided to use it there. For the outside banner, however, I had found a frontispiece that showed a couple in bed where a wife is lecturing her husband who is pretending to sleep in the well-named book of moral tales by Richard Brathwaite, Ar’t asleep husband? A boulster lecture (1640). It was important that our outside banner be both attractive and easily show the theme of the exhibit.

We knew that the cases had to not only have interesting and significant information but also had to be visually interesting. This is perhaps the greatest difference between writing a book, even if it is illustrated, and designing an exhibit. In the case “To Make One Sleep,” for example, we included several manuscript book recipes but also a mortar and pestle and ampoules with ingredients—while we had examples of the actual herbs used, the dormice blood was represented by colored water. As I put it when I did the press tours, “No dormice were hurt or killed in the making of this exhibit.” We also had a case of herbals as the Folger has an extensive and beautiful collection. One was opened to the mandrake, a narcotic plant. The illustration for it shows a plant that looked like a man. In the case on how to control dreams we again had beautiful manuscript recipes. But we also included a lapidary, a book on gems, that explained how emeralds, amethysts, rubies, and onyx could be used to avoid bad dreams, and had actual gem stones in the case as well.

The Haydock and the King James cases worked together as James was the one who exposed Haydock. The Haydock case contained his manuscript written in a beautiful italic hand and facsimiles of several other pages. We also included the Italian art book that the multitalented Haydock had translated. Haydock even designed the frontispiece which included his own self-portrait. James I also wrote about dreams in his book, Daemonologie. The Folger owns a clean manuscript copy James had had made with his own corrections, which was a fascinating addition to the case. In the 17th century a number of political pamphlets, especially around the time of the war between king and parliament leading to the execution of Charles I, used dreams as a way to justify a point of view. These pamphlets also had fascinating illustrations of the dreams they discussed, including several images of the beheading of Charles.

As we worked on the exhibit we kept talking about how we wished we could have an Elizabethan bed set up in the middle of the exhibit hall. While that was clearly impossible, we did create a large case that suggested an Elizabethan bedroom. While we obviously could not have a bed in the case, we had a bed table, a tapestry that might have hung in a bedroom, a treasure box, a water pitcher, and a chamber pot. In the Elizabethan period people had moral aphorisms called poesies painted on the wooden beams near the ceilings and we had beams made with a poesy and put in the case as well. We also had Emma Lehman, a University of Nebraska graduate student who specializes in history of textiles, clothing, and design, make two facsimiles of a Jacobean night gown and night shirt, which added greatly to the exhibit. To make Shakespeare a larger part of the exhibit and to add to the visual appeal we decided to have large photos from Folger Theatre productions of Shakespeare plays that included sleep or dreams, such as Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Macbeth.

One of the most exciting parts of the exhibit was the dream machine, an interactive computer that allowed people to find out what a wide variety of dreams meant in the Renaissance. To make the exhibit even more accessible, we also did recordings about something in each case that visitors to the exhibit could listen to on their cell phones. Just as we had to keep careful count of words in the case and item labels, each audio narrative as well needed to be about 90 seconds in length.

Being part of this exhibit allowed me to work with talented and generous people, to work with sources in a completely different way, to develop some new skills, and to allow the wide range of people who came through the exhibit to learn more about a fascinating aspect of the English Renaissance. I was able to have much to offer the exhibit because I had done so much research on the topic at the Folger and thus was aware of many items we could use. Because of the world wide web even though the exhibit ended in May 2009, it still exists on the Folger Shakespeare Library web site (www.folger.edu/Content/Whats-On/Folger-Exhibitions/Past-Exhibitions/To-Sleep-Perchance-to-Dream) with information on each case, the dream machine, and the audio tour.

Carole Levin is the Willa Cather Professor of History and the director of the medieval and Renaissance studies program at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. She is the author of many books, including Dreaming the English Renaissance: Politics and Desire in Court and Culture (2008).

Tags: Europe Public History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.