News

"So Much to Remember"

Exploring the Rosa Parks Papers at the Library of Congress

On February 4, Rosa Parks’s birthday, the Library of Congress opened to researchers the newest addition to its collection of materials on the civil rights icon: approximately 10,000 personal papers and photographs. Until they arrived at the library in October, the collection belonged to Guernsey’s Auctioneers, where it was inaccessible to researchers.

The history of the collection is well known among Parks and civil rights historians: owing to a legal dispute between Parks’s descendants and the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, a judge ruled that her belongings be disposed of at auction to a single buyer and the proceeds divided among the parties. Guernsey’s became the steward of the papers in 2007, and because the asking price was so high, the papers sat locked away for eight years.1 In August 2014, Howard Buffett of the Howard G. Buffett Foundation purchased the papers for $4.5 million: “This is an incredible part of history, and to have that history locked up is not right,” he told CNNMoney in an interview in August.2 Buffett has loaned the collection to the Library of Congress for 10 years, where it will be available to the public.

The value of this collection cannot be overstated. Although Rosa Parks donated some of her papers to Wayne State University in the late 1970s, those papers can give researchers only a glimpse into her life. The collection at Wayne State, spanning the years 1954 to 1976, consists of six boxes, one of which contains manuscript materials; the others contain papers related to Parks’s activities, associations, and other personal effects.3 In contrast, the collection now available at the Library of Congress contains 40 boxes full of letters, biographical writings, notes, and photographs spanning the years 1866 to 2006.4 This treasure trove of materials makes it possible for scholars to fill in the gaps in what we know about Parks’s life and to get to know her as a lifelong freedom fighter, as opposed to the “accidental heroine” who triggered the Montgomery Bus Boycott by refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man.

Credit: Library of Congress, courtesy of Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development

This photo of Rosa Parks in 1956 captures the idea that there are two images of Rosa Parks—the public icon and the more private woman we see in her papers. The photograph was taken by Gil Baker.

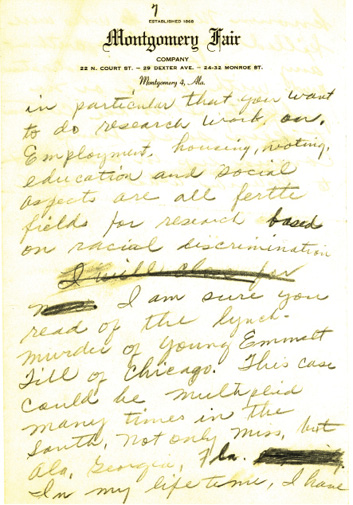

To get an idea of what sort of new insight could be gained from the new Library of Congress collection, I visited the papers in the Manuscript Reading Room. There, I interviewed Margaret McAleer, an archivist who worked on organizing and processing the papers. The 10,000 items had not been organized in any particular way at Guernsey’s but had rather been inventoried item per item.5 In the process of sorting and cataloging the items, McAleer gained an intimate familiarity with their contents. She pointed me to some of the more impactful items she had come across, lingering over some of Parks’s correspondence and writing fragments. “There are parts of the collection that allow us to actually read her voice in a way that I don’t think we’ve been able to ever before,” McAleer reflected. Often enough, this visible “voice” extends beyond the words themselves to the way Parks wrote them. In one draft letter “to a friend,” written on the stationery of the Montgomery Fair department store, Parks writes near the end, “I will close for now,” then scratches out that sentence and proceeds with reflections on the recent death of Emmett Till:

I am sure you read of the lynch-murder of young Emmett Till of Chicago. This case could be multiplied many times in the South, not only Miss, but Ala, Georgia, Fla. [indec. scratchout] In my lifetime, I have known Negroes who were killed by whites without any arrests or investigation and with little or no publicity. It is the custom to keep such things covered up in order not to disturb what is called [ends]6

“By concluding with Emmett Till,” McAleer says, “she’s bringing home the gravity of the situation. It shows how much Emmett Till was in her mind.”

The psychology of Parks can be seen on a larger scale in how much she wrote at different times in her life. McAleer reflected on how during the bus boycotts and in their aftermath, when Parks was busy traveling and speaking, she was exhilarated and constantly writing about her activities. After she and her husband, Raymond, both lost their jobs and moved to Detroit, however, the tone of Parks’s writing changed. She began to write what appear to be biographical fragments, the purpose of which is unclear. McAleer suggests that this relatively quiet period in Parks’s life may have been a time when Parks was “coming to terms” with everything that had transpired.

Civil rights historian Jeanne Theoharis, author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks (2013), knows firsthand how much this collection can add to our understanding of Rosa Parks. Theoharis waited anxiously for Guernsey’s to make the collection available to scholars, but finally gave up and proceeded to write her biography in the hope that its publication might help spur action. Although much is known about Parks’s life from numerous sources—the materials at Wayne State, oral histories, her autobiography with Jim Haskins, news articles, et cetera—she is nonetheless “hidden in plain sight,” said Theoharis in an interview. The events of Parks’s life are well known, but we still only have limited access to her personal thoughts and voice.

Credit: Library of Congress, courtesy of Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development

Parks wrote this draft of a letter to a friend in January 1956, not long before losing her job as a seamstress at the Montgomery Fair department store. Notice the scratched-out writing: “I will close for now,” preceding Parks’s reflections on the death of Emmett Till.

Theoharis and her colleague Julian Bond both made attempts to visit the papers while they were held at Guernsey’s, but the auction house was not granting scholars access.7 Theoharis argued that “Guernsey’s really treated [Parks] like a celebrity” rather than an important historical figure; she said that the house did not invite scholars to appraise the collection, as would be typical with the papers of a person of historical importance. Rather than working from the papers themselves for her biography, Theoharis instead had to use the inventory Guernsey’s had prepared for prospective buyers, which included “teaser” quotes from the documents. It was not until January, when the Library of Congress invited Theoharis to assess the collection, that she finally got to read the papers themselves.

“This speaks to the weird way she’s positioned in American culture,” Theoharis says. “Rosa Parks is one of the most honored Americans of the 20th century. But the ways she’s been honored—reduced to a single act on a long-ago December day—has reduced her, made her small and meek, rather than a fiercely determined person who has a lifetime of political experiences and clear political ideas.”

The papers now at the Library of Congress can help scholars combat this limited image of Rosa Parks. Theoharis spoke of all sorts of details about Parks’s life that “would have been more vivid” in her book had she had access to these documents: she likened the experience of reading the papers themselves to adjusting the focus in a camera to get the image “sharp and bright.” For instance, political activists described to Theoharis how the “feisty” Parks, a petite woman, would drive to “black power” meetings in a very large car; however, this was not the kind of anecdote that could really be envisioned until Theoharis discovered a specific reference to the car in the papers: “a white 1965 Ford two-door HT weight 2997 that she buys from her brother in 1968.” A small detail, yet one that contributes to a fuller, more human picture of Rosa Parks.

The papers also force us to deal with the extreme degree to which Parks and her family suffered in the years following her famous act of resistance. They include numerous financial papers, which, according to Theoharis, reveal “how stark it is, how much she’s worrying, how they’re constantly trying to move money around.” Theoharis cites an incident when Parks and her husband, Raymond, could not make a down payment on a refrigerator they were trying to purchase from a warehouse, arguing that these are details we have not acknowledged as much as Parks’s more public, heroic aspects.

Nor have we entirely acknowledged the extent of Parks’s loneliness as a civil rights activist and the emotional toll of the events in which she was embroiled. A fragment of what appears to be a brief poem reads,

Hurt, harm and danger

The dark closet of my mind

So much to remember8

Writings like these grant us a glimpse into what McAleer describes as Parks’s “interior psychological space”—something that only the most personal of papers can really communicate, and a subject that makes the heroine distinctly human. This is the Rosa Parks Americans should attempt to know better, and with Howard Buffett’s enormous contribution in purchasing the papers and the Library of Congress’s alacrity in organizing and cataloging them, they are now ready for researchers eager to learn more. The library held a temporary exhibit of selected items from the Parks Papers from March 2 through March 30, 2015. Three of these items, among them a date book with notes about the bus boycott in 1956, were also included in the ongoing exhibit The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom, now open to visitors.

Stephanie Kingsley is the AHA’s associate editor, web and social media. She tweets @KingsleySteph.

Notes

1. Julian Bond and Jeanne Theoharis, “Why Don’t Scholars Have Access to Rosa Parks’s Archives?” Washington Post, August 29, 2011,

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-dont-scholars-have-access-to-rosa-parkss-archives/2011/08/29/gIQAKezHoJ_story.html.

2. Richard Barbieri and Poppy Harlow, “Why Buffett’s Son Bought Rosa Parks Archive,” CNNMoney, August 31, 2014,

http://money.cnn.com/2014/08/31/news/economy/howard-buffett-buys-rosa-parks-collection/.

3. “Rosa L. Parks Collection: Papers, 1955–1976,” finding aid, Wayne State University,

http://reuther.wayne.edu/files/UP000775.pdf.

4. Margaret McAleer, Kimberly Owens, Tammi Taylor, Tracey Barton, and Sherralyn McCoy, Rosa Parks Papers: A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress (Washington, DC: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, 2014).

5. For more on the herculean feat of processing the Rosa Parks papers in two months, see Meg McAleer, “A Sense of Purpose: Organizing the Rosa Parks Collection,” Library of Congress Blog, February 11, 2015, http://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2015/02/a-sense-of-purpose-organizing-the-rosa-parks-collection/.

6. Box 18, Folder 10, Rosa Parks Papers, Library of Congress.

7. Bond and Theoharis, “Why Don’t Scholars Have Access to Rosa Parks’s Archives?”

8. Box 18, Folder 11, Rosa Parks Papers, Library of Congress.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Tags: History News Archives African American History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.