Masters at the Movies

Through a Lens Darkly: Oliver Stone's Wall Street

Gordon Gekko is back. After a bravura performance in the 1987 film, Wall Street, Oliver Stone decided it was time for Michael Douglas to make a sequel. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps came out in fall 2010, just in time to join the avalanche of books explaining what happened on Wall Street when the financial center lost its center of gravity two years ago. Gekko, of course, has already entered American folklore with his remark that “greed is good.”

Gordon Gekko is back. After a bravura performance in the 1987 film, Wall Street, Oliver Stone decided it was time for Michael Douglas to make a sequel. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps came out in fall 2010, just in time to join the avalanche of books explaining what happened on Wall Street when the financial center lost its center of gravity two years ago. Gekko, of course, has already entered American folklore with his remark that “greed is good.”

Ironically, the 1987 Wall Street gives a much better idea than its sequel of what went wrong in the American economy in 2008. This is because the initial film had to explain why Gekko got so powerful whereas the second film could take that for granted and make the financial world conform to the exigencies of plot. The first Wall Street captured the frenzy that reigns in a stock brokerage firm where young and not-so-young traders sit cheek by jowl each day touting stock trades. They make mind-numbingly repetitious calls, punctuating their ceaseless telephoning with breaks spent high-fiving each other or spreading rumors.

It was in the turbulent waters of such a fishbowl that brokers, bankers, and hedge fund managers launched the thousand risky, asset-backed derivatives that brought down Lehman Brothers. When the U.S. government failed to save this venerable bank, the incredibly tight “sink-or-swim together” union of world financial institutions became apparent. So much so that the Bush administration quickly shifted into high gear to head off disaster.

Because they are crafted as morality tales where heroes and villains call the shots, both pictures leave the viewer without any understanding of why this madcap world collapses. The 2008 financial crisis had two underlying causes complicated by a wild card. The first was set in place in the late 1970s when a recession stirred interest in eliminating regulations that the New Deal had put in place. Writers began depicting capitalist enterprise as a Gulliver tied down by a thousand Lilliputian strings from safety monitors, environmentalists, and the like. While legislatures were deconstructing the regulation of banks, brokerage houses, and insurance companies, an unusual amount of money was sloshing through global markets. High rates of saving among people in Asia’s developing nations greatly augmented the amount of capital seeking investments. This led to reduced interest rates, which were further pushed down by the government’s efforts to stimulate the economy.

Unhappy with rates in the 2–3 percent range, the mavens of finance, whom Stone features in his two movies, began thinking up ways to boost that return. A boom in housing in the United States gave them the opportunity they were looking for. They contrived a dicey array of new financial investments. Bank mortgages were divided up and turned into derivative securities. Soon these securitized mortgages passed from commercial to investment banks where they were repackaged and sold to investors or other banks, a program so promising they extended it to those notorious subprime mortgages issued to people with poor prospects of meeting their payments.

The wild card in this scenario was the endemic confidence that encouraged institutional investors and hedge fund managers to purchase the new asset-backed securities. In retrospect their misperception of the risk seems bizarre, but optimism laced with fantasies of outsized bonuses had become contagious. This infectious spirit among traders and investors introduced a degree of risk that impinged on the whole global economy because of the easy access the world’s investors had to these “good deals.” We might dub this the world of virtual investment whose material reality was a stream of electronic messages issuing from some 60,000 terminals around the world. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps alludes to securitized and subprime mortgages, but not in a way that the uninitiated could understand. Of course, miniexplanations of abstruse assets can be real plot-cloggers, so this is understandable.

Year-end bonuses on performance furnished a further incentive to expand creative financing. During the last 10 years, financial services grew from 11 percent of our gross national product to 20 percent. Some otherwise sober men and women were able to leverage at a ratio of 1 to 30 for money invested, spreading risk without tracking it. More damaging to the nation in the long run, physicists, mathematicians, and computer experts were drawn away from their callings to join the financial high-wire artists. A totally unintended consequence was that the testosterone-driven competition—nicely captured in the first Wall Street —became so intense it prevented looking at the larger picture or listening to the naysayers.

In the early years of the 21st century, 40 percent of Ivy League graduates went into finance where they learned the logic that they should profit handsomely from what they were able to sell for their company, or “eat what they killed” in insider lingo. With million-dollar annual incomes commonplace, Wall Street formed a tight little winners’ circle where all the incentives were thrown on the take-more-risk side and positive disincentives discouraged caution or even candor.

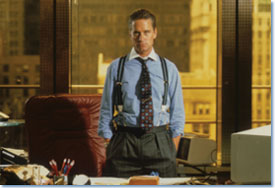

This is the world that young Bud Fox (played by Charlie Sheen) enters in the 1987 Wall Street. He leaves behind the milieu of his father, a strong union man. Fox wants to move up and out of the floor of jangling telephones, so he takes some insider knowledge that he gleans from a conversation with his dad to the kingpin of this craziness, Gordon Gekko. Gekko sees that he can make a killing by destroying the small airline company that Fox’s father works for, and Fox gets an eye-opening lesson in how to be successful. From a historical perspective, this narrative conforms well with the actual shenanigans that went on during the 1970s and 1980s when racketeering and securities fraud made headlines. What never comes out—and it’s a little difficult to see how a Hollywood film could depict structural changes—is the new role of capital. From being the necessary handmaiden to production, capital became the lead player, flowing across national boundaries and making its managers the global economy’s kingpins.

But Stone does capture in this film the frantic pace and lazy cynicism of Wall Street. His cinematography of close-ups flashing by suggests the pace that jangles nerves on the floors of the stock exchange and its satellites in brokerage firms. We realize that we’re in a different world when we hear Bud Fox explaining to his father how easily his $50,000 annual salary slips through his fingers. When Gekko returns to audiences 23 years later, he’s engaged in mortal combat with an egomaniac like himself. Aside from featuring the destruction of a bank with similarities to Lehman Brothers, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps doesn’t shed much light on the 2008 meltdown, for it was occasioned by failures in an entire system, not the machinations of a few titans, Bernard Madoff notwithstanding.

Curiously, these two movies about the most sterile of workplaces actually pivot around families—the relationship of fathers and sons in the first and Gekko with his daughter in the 2010 film. The Bud Fox character convincingly conveys his love for his father, conveniently played by another Sheen, Charlie Sheen’s actual father, Martin. Yet Bud Fox gets swept up by the attention that Gekko showers upon him. Since he’s not the bright penny in Gekko’s pocket, Fox seems to be tapping into Gekko’s paternal instincts, not fully engaged by his toddler son.

Much happened to Gekko in the 23-year interlude. His marriage has ended in divorce; he has served a prison term; his son has died of an overdose, and his daughter will have nothing to do with him. Stone draws on family relations again to breathe some life into a movie about finance. The fiancé of Gekko’s daughter, also a trader, commits himself to bringing father and daughter together. He eventually succeeds, a rapprochement sealed when Gekko’s daughter signs over an old Swiss trust to her father on the assumption that she’s avoiding taxation when, in fact, she is giving her father the millions to make a comeback after his post-prison snubbing by the denizens of Wall Street. If it sounds far-fetched, that’s because it is.

If Gordon Gekko thinks that greed is good, Oliver Stone definitely does not share his opinion. He exaggerates the crassness in the financial center to induce the audience to loath everything connected with it. Characters speak for him when they talk about the superiority of creating something instead of living off the buying and selling of others. Damning too is the emphasis that the main thing about money is that “it makes you do things that you don’t want to do.” But if Stone is full of stern warnings, he also delivers happy, Disney-type endings.

In the 1987 film the hero snatches the company his father works for from Gekko’s clutches. The movie ends with Fox walking up the stairs of the New York City courthouse, presumably to get a dose of paternal justice for his inside trading. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps concludes with Gekko, the wicked traducer of a loved one’s faith, magically reconciling his daughter to her fiancé after the fiasco.

Stone’s scarcely veiled contempt for the weird heights of high finance raises the question of how well indignation and drama mix. His depictions of the Street are accurate, but they teeter dangerously on the precipice of caricature. But, alas, our financial center lends itself to melodrama.

Joyce Appleby (UCLA, professor emerita) was president of the AHA in 1997. Her many publications include the 2010 book, The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism. She is a cofounder of the History News Service described in a December 2010 Perspectives on History article.

Tags: Scholarly Communication North America

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.