News

Barely Keeping Up? The 2007-08 Salary Report Suggests History Salaries Are Closing the Gap

History salaries almost kept pace with the rest of academia in the academic year just coming to an end, as the average salary for historians increased 4.33 percent, lagging just slightly behind the increase of 4.37 percent for faculty in all disciplines. While this may seem little cause for celebration, this is actually the first year in the past five that average history salaries managed to come so close to the average salary growth in academia.

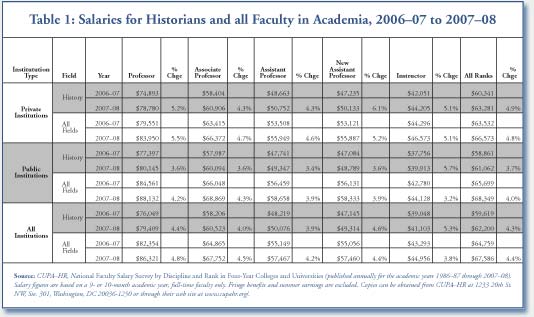

Historians employed full time in academia earned an average of $62,200 in 2007–08, according to a new report published by the College and University Personnel Association–Human Resources (CUPA-HR).1 Beneath the broad averages, however, the report identifies significant disparities between historians at different types of institutions and at different ranks (Table 1).

The average salary for historians at public colleges and universities was 3.6 percent lower than the average for historians at private institutions ($61,062 as compared to $63,281). In comparison, among all disciplines the salary gap is reversed—higher average salaries were earned at public colleges and universities, where the average salary was 2.6 percent above those earned at private institutions ($68,349 as compared to $66,573).

But the disparity between history salaries at public and private institutions largely seems to benefit senior faculty in the discipline, since it is only at the full professor level that historians at public institutions earn more than their counterparts at private colleges and universities. Full professors earn 1.7 percent more at public institutions, while associate professors earn 1.4 percent below the average at private colleges and universities; and assistant professors earn 2.8 percent less.

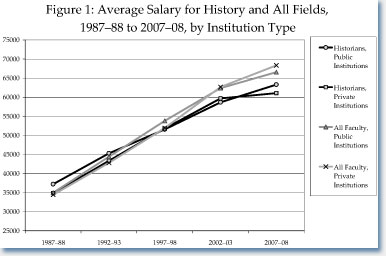

Twenty years ago, history faculty at both types of institutions did better than the average for all disciplines, but the discipline's financial advantages have been waning ever since (Figure 1). In 1987–88, the average historian at private colleges and universities earned 6 percent above the average for all disciplines. At public institutions, historians enjoyed a more modest 1.1 percent advantage.

But over the intervening years, salary increases for historians lagged well below the average. Today average history salaries at all ranks are only modestly higher than those in a few other humanities disciplines (such as English and foreign languages). To the extent that salaries can be seen as a measure of the discipline's relative value in academia, these figures are exceptionally disconcerting.

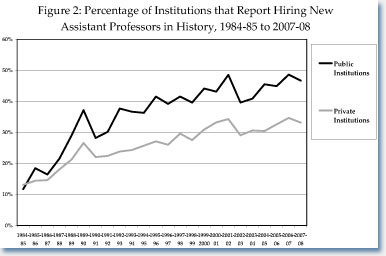

Another troubling indicator in this year's report is a 4.3 percent decline in the proportion of departments hiring new assistant professors for the current academic year (Figure 2). Despite the decline, almost a third of the institutions surveyed reported at least one new historian on faculty, which was the third best year for hiring in the 23 years we have been tracking this data.

The decline was slightly worse at private institutions, which posted a 5.9 percent decline in the proportion of institutions hiring. In real terms, the private colleges and universities in the survey hired 114 new assistant professors (down from 120 the year before), while the public institutions hired 228 new assistant professors (which was actually up from 222).

These numbers should be read with some care, however, since only 702 institutions with history departments participated in the CUPA–HR survey. But over the past 20 years this report has provided one of the better indicators of hiring in the discipline. In the depths of the crisis in the history job market in the 1990s, barely a quarter of the departments were hiring new assistant professors, and in the post-9/11 recession, hiring in history departments plunged. As many states are cutting their funding for higher education this year, we will watch these numbers closely.

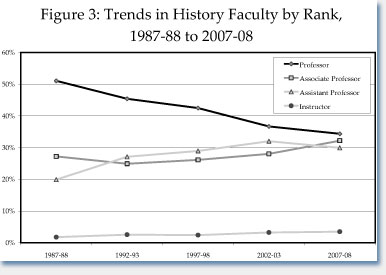

The result of all this new hiring over the past 15 years is a significant change in the demographics of the faculty in history classrooms, as full professors constitute barely a plurality of the faculty in departments (Figure 3). The balance in the professorial ranks in the discipline is near parity now, constituting just a bit over 30 percent at each rank. As the assistant professors hired in the demographic bubble of the 1990s gained tenure, the number of historians at the associate professor level has grown in recent years, and now constitutes the second largest rank in the discipline.

Two decades ago, full professors accounted for more than half of the history faculty in the country. At the time, staff at CUPA-HR singled out our discipline for having so many senior faculty in the department. The recent shift to younger, less senior faculty in history departments helps to explain some of the profession's declining average salaries.

As a larger proportion of associate professors ascends to the next rank, it seems reasonable to hope that average salaries for the discipline will again gain some ground—both because there will be a larger number of faculty in the top ranks, but also because a greater number of senior faculty should bring increased institutional power and leverage to the discipline.

But it also remains to be seen whether the declining salaries of the recent years will become characteristic for the next generation of history faculty. The lower starting salaries for junior faculty during the past 15 years have meant that any raises they received as they rose up through the ranks have also remained low and thus kept salaries at the tenured ranks relatively depressed. This depressed state can also be attributed at least in part to the problems of negotiating starting salaries in a saturated job market for historians. And it may also be the result of our changing disciplinary alignments. Compensation for history faculty seems to have declined in step with history's move from an alignment with the relatively well-compensated social sciences to a closer relationship with the humanities, which have some of the lowest salaries.

—Robert Townsend is the AHA's assistant director for research and publications.

Note

1. Salary figures are based on a nine- or ten-month academic year, for full-time faculty only. Fringe benefits and summer earnings are excluded. CUPA-HR, National Faculty Salary Survey by Discipline and Rank in Four-Year Colleges and Universities for the 2007–08 Academic Year (Washington, D.C.: CUPA-HR, 2007). Copies can be obtained from CUPA-HR at 1233 20th St., NW, Ste. 301, Washington, DC 20036-1250 or through the web site at www.cupahr.org.

Tags: Job Markets

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.