Teaching

Clicking for Clio: Using Technology to Teach Historical Thinking

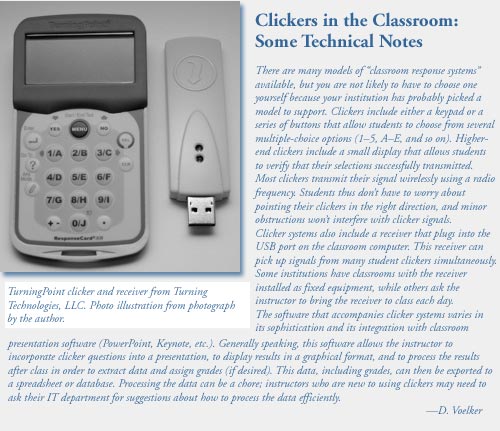

From the point of view of most historians, multiple-choice questions are at best a necessary evil—perhaps useful for quizzes and exams in large lecture courses, but otherwise out of step with our disciplinary habits of mind. At first glance, then, student response systems, known as “clickers,” would seem to be of limited use in history courses. A clicker is a device resembling a pocket calculator that allows students to wirelessly submit answers to multiple-choice questions provided in class by an instructor. There are many different clicker systems, but the most sophisticated systems allow an instructor to embed questions in PowerPoint slides, poll a classroom full of students, and immediately display results in the form of a bar graph, which shows what percentage of the class chose each response. The most obvious use for this technology is to apply it to a familiar task—giving quizzes—but to use clickers primarily for giving paperless quizzes is to mistake their full potential. When deployed openly in the classroom, multiple-choice questions can take on new pedagogical functions. Unlike quiz and exam questions, multiple-choice questions used in class need not have a single correct answer. The true pedagogical promise of clickers lies in using the questions (and the answers) as a starting point for discussion of historical evidence and interpretations rather than as an ending point for evaluating student knowledge. Clicker questions can thus help instructors pique student interest, address misconceptions, and spur analysis of primary and secondary sources, particularly in introductory-level courses with large enrollments.

From the point of view of most historians, multiple-choice questions are at best a necessary evil—perhaps useful for quizzes and exams in large lecture courses, but otherwise out of step with our disciplinary habits of mind. At first glance, then, student response systems, known as “clickers,” would seem to be of limited use in history courses. A clicker is a device resembling a pocket calculator that allows students to wirelessly submit answers to multiple-choice questions provided in class by an instructor. There are many different clicker systems, but the most sophisticated systems allow an instructor to embed questions in PowerPoint slides, poll a classroom full of students, and immediately display results in the form of a bar graph, which shows what percentage of the class chose each response. The most obvious use for this technology is to apply it to a familiar task—giving quizzes—but to use clickers primarily for giving paperless quizzes is to mistake their full potential. When deployed openly in the classroom, multiple-choice questions can take on new pedagogical functions. Unlike quiz and exam questions, multiple-choice questions used in class need not have a single correct answer. The true pedagogical promise of clickers lies in using the questions (and the answers) as a starting point for discussion of historical evidence and interpretations rather than as an ending point for evaluating student knowledge. Clicker questions can thus help instructors pique student interest, address misconceptions, and spur analysis of primary and secondary sources, particularly in introductory-level courses with large enrollments.

Classroom Strategies

A well-planned clicker question can be a great way to introduce students to a problem or question that will structure a class session. For example, the instructor can ask a polarizing question (controversial either among the general public or among historians) as a way to get students to individually stake out a starting position. Asking a question such as, “Was the African American civil rights movement of the 1960s successful?”—and providing a spectrum of answers—can be an effective way to get students thinking about a subject by having them converse in small groups, with assigned partners, or in ad hoc pairs before they click in a response. (This particular question, of course, can lead, in turn, to discussion of other important issues, such as what “successful” means in that context.) Furthermore, such a poll gives instructors an idea of where students stand, which may help with setting priorities for the session, and the poll may be repeated later to see how students’ views have shifted.

Clicker questions can help instructors deal with another preliminary problem: drawing out student misconceptions. Students are understandably reluctant to risk seeming ignorant in front of their instructor and peers. But misconceptions must be dredged up and addressed to allow student understanding to grow.1 Clickers provide a way to figure out what your students already know so that you can reinforce accurate pre-existing knowledge and correct misconceptions. For example, when my students were studying the American Revolution, many were led astray by their preexisting knowledge of the principle of “no taxation without representation.” I had read an excerpt from the 1765 “Declaration of Rights” issued by the Stamp Act Congress, wherein the aggrieved delegates not only denied that parliament could tax the North American colonies but also argued that they could not be represented in parliament because of the long distance that separated them from England. Nevertheless, when I asked students via a clicker question two days later, fully 60 percent of them supported the erroneous notion that colonists wanted to send representatives to Parliament. This result gave me the opportunity to ask students why they had picked the incorrect answer and to explain again the political theory that lay behind the colonists’ actual positions. When I repolled this question several days later, 80 percent of students answered it correctly. In this particular case, I had preemptively addressed the misconception with an illustration from a primary document, but it was not until I also used the clicker question that most students managed to correct their misconception. Instructors cannot anticipate every misconception, of course, but I have found that unexpected responses to clicker questions often help me identify and address these unforeseen barriers to improving student understanding.

Discussing the questions and answers also allows students to practice skills of historical analysis. After displaying the results of each poll, I usually invite the whole class to discuss each response by asking students why they picked (or could have picked) the various answers. In other words, I ask them to consider the evidence that is relevant to the question. They learn that they cannot simply state unprocessed facts; they need to explain how and why the information that they have supports a particular answer. (Students have reported on a survey that developing this skill of supporting a historical claim helps them succeed on my exams, which require them to argue both for and against a historical statement.)2

Discussing the questions and answers also allows students to practice skills of historical analysis. After displaying the results of each poll, I usually invite the whole class to discuss each response by asking students why they picked (or could have picked) the various answers. In other words, I ask them to consider the evidence that is relevant to the question. They learn that they cannot simply state unprocessed facts; they need to explain how and why the information that they have supports a particular answer. (Students have reported on a survey that developing this skill of supporting a historical claim helps them succeed on my exams, which require them to argue both for and against a historical statement.)2

Just as important as supporting the correct or best answer, however, is the process of discussing why the “wrong” answers are inferior to the best answer. In fact, discussing incorrect answers is often very productive, because doing so provides an opportunity to address both the logic and evidence behind historical thinking. Talking over an incorrect or inferior answer with my students allows me to get a window into how they are thinking about the issues at hand and to address misconceptions that I may or may not have foreseen. Often, I ask students to explain why someone might choose one of the problematic answers—what is to be said for it?—but I also make sure that we uncover the shortcomings of these wrong or less accurate answers. By discussing why these answers are weaker or by ranking the answers according to their relative strength, I attempt to develop their abilities to think like a historian.

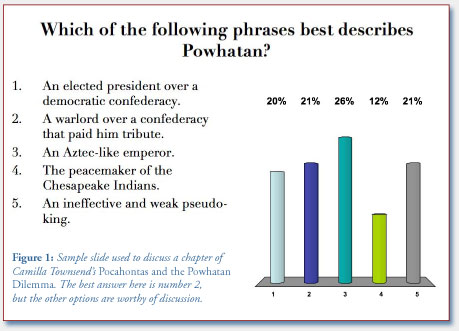

Clicker questions can also help with the persistent challenge of facilitating a discussion of primary and secondary readings with large numbers of students. For example, when my students read Camilla Townsend’s Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005), I ask them to pair up to discuss her characterization of Powhatan, the leader of the Chesapeake Indians (see Figure 1). In this case, I withhold the answer options until students have discussed the question, in order to encourage them to formulate an answer on their own. After they vote, we thoroughly discuss the evidence behind their positions, which allows us to work together to draw conclusions. In many instances like this one, a clicker question can serve as a point of departure for an extended discussion of an assigned reading.

Logistical Matters

It does not take many clicker questions per session to change the pace of a course by facilitating more interaction among students and between students and the instructor. Questions can be distributed throughout a class in order to repeatedly refocus student attention, which we know tends to drift in response to relentless lecturing. I have found it helpful to use one or two questions at the beginning of class to review from the previous meeting and set the stage for the session, one to three questions in the middle of class to discuss readings and key concepts, and one or two questions at the end of class to review the main points we have considered. For a 60-minute class, three or four questions might be plenty; for a 75-minute class, five or six questions will usually be enough.

Fully discussing several questions may take 15 minutes or more of class time, but this time is hardly wasted. Even reserved students who do not talk in front of the whole class can share their ideas with someone sitting next to them, while more talkative students will test out ideas that they can then share with the whole class. There is, however, a potential pitfall to be alert to: some students might see the clicker as a license to be passive; having voted, they may then elect to sit silently. To avoid this problem, one needs to make a concerted effort to use clickers to promote discussion during the very first class sessions.

If you are interested in trying clickers in your classroom, check with your institution’s information technology (IT) office, which may already support a particular platform. If your institution does not support clicker technology, you can still have students purchase clickers (some textbook publishers bundle clickers with textbooks). This approach is less than ideal, though, because you will be required to provide technical support to your students if they encounter any problems. From a technical standpoint, however, the most significant challenge associated with clickers is data management. Counting clicker participation as 15–20 percent of the course grade can be a very effective way of improving and rewarding class attendance, but it also means that you will have to very carefully track the points that students earn.3 Unless you are especially handy with spreadsheet or database software, you may need to get help from your campus IT staff to set up a reliable system for tracking student points.

Conclusion

Introducing clickers into a course can be a demanding task, not only because of the extra time needed to create effective question slides but also because of the need to process a significant amount of data. It still remains for a historian to undertake a scholarship of teaching and learning project to systematically study the application of clickers in the history classroom, but in the meantime, having experienced the immediate feedback about how my students are thinking and understanding course material, I find clickers hard to dispense within my own introductory courses.

—David J. Voelker is an associate professor of humanistic studies and history at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. His article, “Blogging for Your Students,” appeared in the May 2007 issue of Perspectives. He can be contacted at voelkerd@uwgb.edu.

Notes

1. On the importance of addressing preexisting knowledge, see Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, Understanding by Design, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education, 2006), 50–55.

2. See David J. Voelker, “Assessing Student Understanding in Introductory Courses: A Sample Strategy,” History Teacher 41 (August 2008): 505–18. 3. For a sample syllabus that explains how clicker-based participation fits into one of my courses, see www.uwgb.edu/voelkerd/syllabi/clickers.pdf.

Tags: Teaching Resources and Strategies

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.