News

Two Historians Receive 2008 Kluge Prize for Study of Humanity

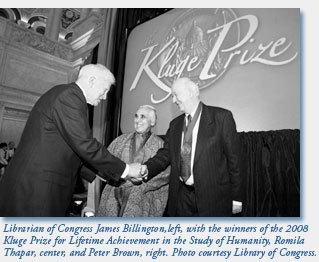

In a ceremony held on December 10, 2008, in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, historians Peter Robert Lamont Brown and Romila Thapar were presented the 2008 Kluge Prize for lifetime achievement in the study of humanity. They are the sixth and seventh recipients since the inception of the prize in 2003. Each awardee will receive half of the $1 million prize, which has been conferred upon such distinguished scholars as Leszek Kolakowski, Paul Ricouer, and John Hope Franklin.

In a ceremony held on December 10, 2008, in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, historians Peter Robert Lamont Brown and Romila Thapar were presented the 2008 Kluge Prize for lifetime achievement in the study of humanity. They are the sixth and seventh recipients since the inception of the prize in 2003. Each awardee will receive half of the $1 million prize, which has been conferred upon such distinguished scholars as Leszek Kolakowski, Paul Ricouer, and John Hope Franklin.

Brown and Thapar were recognized for bringing new perspectives to understanding vast sweeps of geographical and temporal terrains, Brown in looking at Europe and the Middle East, and Thapar in considering the Indian subcontinent. While reimagining familiar worlds they opened large areas of human experience to new historical inquiry, and addressed their scholarship not only to specialists, but also shared their insights with broader lay audiences.

Commenting on Peter Brown, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington said: “He is one of the most readable and literary historians of our time, having brought to life both a host of fascinating, little-known people from ordinary life during the first millennium of Christianity, as well as a monumental biography of the most prolific and famous St. Augustine.”

One scholar reviewing nominations for the Kluge Prize wrote: “Peter Brown ranks with the greatest historians of the last three centuries.” Another said: “There are few scholars in the world today who have changed their fields as much as Peter Brown has changed the study of what we used to call ancient and medieval history.”

Through his careful scholarship, Peter Brown eloquently and lucidly illuminated the world of late antiquity and has reformulated the history of the Mediterranean world from the 2nd or 3rd century to the 11th century C.E., as a coherent historical period marked not by the tragic death of an old civilization but by the difficult birth of a new one. Using a vast range of sources, visual as well as verbal, he described the evolution of pagan philosophy and the rise of Christianity as part of a single social world. He also traced the story of late antiquity forward into the rise of new empires and civilizations in Persia, the Islamic world, and in Byzantium as well as Western Europe.

Remarking on Romila Thapar, Billington said: “She has used a wide variety of ancient sources and of languages, and introduced modern social science perspectives to help us better understand the richness and diversity of traditional Indian culture. And she, like Brown, has written a great biography of one of its giants, the Buddhist emperor Asoka."

Her prolific writings have set a new course for scholarship about the Indian subcontinent and for the writing of history textbooks in India. One scholarly reviewer said that “Thapar’s rigorous professional standards are cast against a background of her implicit appreciation of an India that accommodates civilizational diversity.” Another said: “Thapar’s relentless striving for historical truth—independent of the superimposition of vacillating, fashionable theories of current sociopolitical conditions—is a landmark in the global writing of history.”

The pre-eminent historian of early India, Romila Thapar, emeritus professor at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, formulated new questions about the social development of nearly 2,000 years of Indian history and challenged existing historiographic paradigms. Making innovative use of familiar archeological and literary sources and mining new data from multiple sources, she produced new interpretations of Indian history. Her iconoclastic approach stirred up controversy, but the cutting-edge research that she and like-minded colleagues advanced—and which has percolated into school history texts as well as public consciousness—profoundly changed the way India’s past is understood both at home and across the world.

Brown and Thapar are expected to return to the Library in 2009 to present a scholarly discussion of their respective bodies of work.

Endowed by Library of Congress benefactor John W. Kluge, prize is international.

Kluge—who spoke at the ceremony after a video honoring his vision and philanthropy was screened—said, “The recipients are the important people because they have dedicated their life to their scholarship.”

—Based on a press release from the Library of Congress

Tags: History News

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.