For the past 15 years, the American Historical Association has been struggling to balance its mission to address diverse topics and a wide public with the more mundane need to fund its activities. Our move onto the internet 13 years ago significantly improved our ability to achieve our mission, while, at the same time, creating new economic risks—risks that seem all the more troubling in these worrisome financial times.

Looking back to the beginning of the Association, publishing was a core activity that helped to shape the organization’s central mission. When we went to Congress in 1889 seeking an official charter, we articulated a clear and explicit mission for the organization as being “for the promotion of historical studies, the collection and preservation of historical documents and artifacts, and the dissemination of historical research.”

As a secondary benefit of the congressional charter, the AHA began publishing its annual reports through the U.S. government’s printing office. While that might sound like a fairly modest undertaking, we exploited that arrangement to the hilt. Some of those reports ran to over 1,500 pages across two or three volumes. They incorporated collections of documents, reports on a wide range of historical practices, and a few full-length monographs.

This relationship with the Government Printing Office established a parasitical model of publishing, which has proven to be an essential aspect of our program ever since. From 1895 to 1945 we supplemented the annual reports through publishing arrangements with various commercial publishing houses. And since World War II, we have worked primarily with university presses. Over the past 15 years, for instance, we have co-published books and serials with the university presses at Chicago, Columbia, Illinois, Oxford, and Temple.

Regrettably, I think, the Association set many of the wider goals as articulated in the charter behind between the last world war and the 1980s, as the leaders of the Association focused most of their attention and resources on serving the interests of faculty at elite research universities, and the American Historical Review represented almost the entirety of the Association’s publishing program. With the exception of the short-lived Service Center for Teachers, the interests of teaching and the gathering of primary source materials devolved to relatively minor committees in the AHA and other organizations.

It was really only in the late 1980s that we began to shift back to the larger mission for the organization by developing a print publishing program that addressed the larger range of history work. The AHA Newsletter became Perspectives, for instance, and was increasingly oriented to serve as a complement to the AHR (with the former addressing the practice of history while the latter disseminated new scholarship). And with a move onto the internet in 1995, we began to reach out to a wider and more general audience, attempting to fulfill some portion of the Association’s larger mission.

Within the headquarters office, a significant amount of our time is taken up on the production of a monthly magazine, Perspectives on History, though the line between the magazine and our other publications has become quite blurred. We regularly raid the magazine for articles for edited collections, and post much of the content online. Alongside the magazine, we also publish 6 to 10 pamphlets each year, which are either short monographs, or explore some aspect of professional work.

Our other major publication is the Directory of History Departments, Historical Organizations, and Historians in the United States and Canada. The Directory provides a useful model of the synergies we have tried to achieve between our print and online publications. The editorial operation for the print book—which consumes a large portion of the summer for much of the publications department staff—now provides content for three online database sites: a quick look-up database for information for departments, a comprehensive database of history dissertations (in progress as well as those completed), and a comprehensive database of information on history doctoral programs. The content is developed as part of that operation, and also largely subsidized by the fees for the print book.

These databases are part of a much larger internet publishing program, which consists of a variety of Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 endeavors. Our web site currently consists of about 24,000 static pages, and half dozen data-driven sections. This web site accounts for most of our inbound traffic, drawing an average of about 30,000 unique visitors each week.

Alongside the primary web site, in 2006 we launched a blog, AHA Today, which broadcasts news and information about the profession and the Association. Thus far we have managed to sustain an early commitment to post at least one item each day during the business week. As you might imagine, the commitment to continual posting can be a bit of a distraction from other activities in the department, but we have been quite pleased with the amount of interest it draws to the Association and its activities. At this point we attract an average of about 2,000 visitors per week, though we do not have a firm count on the number of people receiving it through RSS feeds.

Lastly, in February 2008, we launched ArchivesWiki, which is designed to get historians and archivists to share inside information about where and how to do research. We are still waiting to see whether this will be much of a success, but once again, it seems to have brought us significant public interest and attention. At present this is attracting about 200 visitors each week.

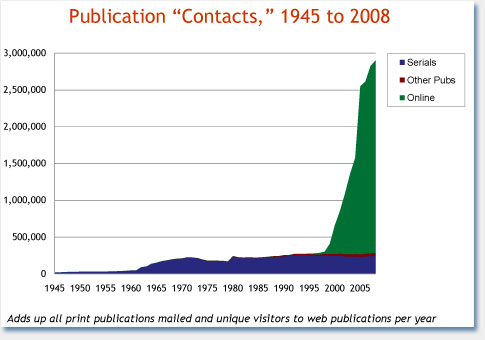

Taken collectively, our online publishing program has significantly extended our reach. It might help to demonstrate the effect the web has had on the execution of our mission by a simple count of the number of publication “contacts”—which is to say the number of times someone received something we consider a publication—either in print or on the web (Figure 1). Over the past 20 years distribution of our serials (including both the AHR and Perspectives on History) to members and subscribers has been pretty stable at about 240,000 units per year. Our other print sales have tripled from about 12,000 units sold when I started here in 1989, to just over 39,000 last year. But when we also count the number of unique visitors we are reaching annually through the Web, our total reach has increased substantially, to almost 3 million contacts per year. If you combine our print subscribers with the number of unique visitors we get on our site, we have more than tripled the number of people who have some contact with the Association each month.

It has taken a wide variety of content to draw that many visitors to our site—most of it made available for free. In addition to search terms directly related to the AHA, readers are also drawn by other content that we have digitized from our archive of print publications. For instance, if you type “what is propaganda” into Google, the second listing in the results is a digitized version of a pamphlet the AHA produced for the U.S. War Department during World War II. Evidently, the diverse range of content is enabling us to reach and attract a global audience. We are happy to count that as a significant success in our efforts to fulfill our mission, while also publicizing the AHA “brand.”

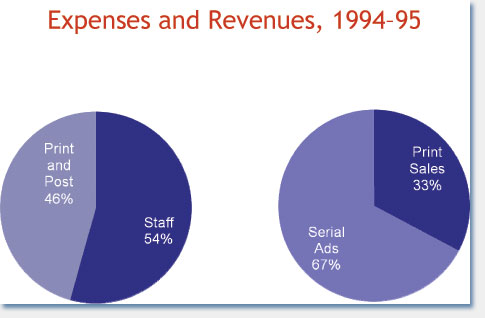

But behind every silver lining there is a dark cloud, and in our case, that is the imbalance between revenues and expenses. If we set aside revenue and expenses from the American Historical Review, which is treated as a separate cost center in our budget, the picture of revenues and expenses for the AHA’s publications department 13 years ago was as shown in Figure 2. In the year before we went online, we spent almost half a million dollars on publications, and earned about four-fifths of that back in revenues through sales and advertising. Although the chart does not clearly show it, revenues were $106,000 lower than expenses, with the gap filled by membership dues.

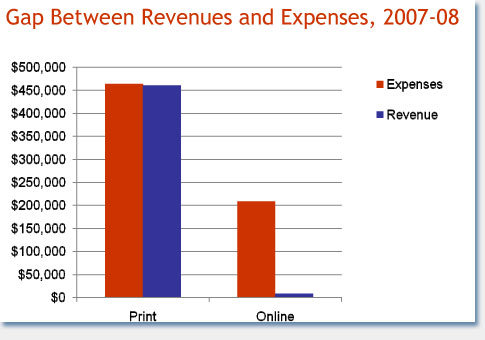

As we jump ahead to the present, you will see how the contours of our expenses have changed, even though our total budget line has only kept pace with inflation. The costs of staffing and software for our various web publications has now grown to almost a third of the total costs in the publications department. But while online publication is now consuming 31 percent of our operating expenses, our various web publications are only bringing in 2 percent of the revenue.

From Figure 3 you can see that the gap between revenues and expenses now stands at about $200,000, primarily due to the online publishing operation. So while the pie has essentially remained the same, our costs have shifted considerably. Currently we depend on membership revenues to fill in the growing gap between costs and expenses. And to help keep the numbers even this close, we have had to cut back on our print-related expenses—in part by finding new economies in short-run printing; and in part by shifting some print publications, particularly our directories, over to the web site where they can also be more effective as databases without the added cost of paper. And some economies have also been achieved by reusing content in multiple media and squeezing more productivity out of the staff.

So we seem to be approaching a difficult position. Even though we are doing a better job of advancing our mission, by making more of our current and back content available to a wide audience online, the benefits are less tangible than the very real costs. As a result, the publications department seems precariously positioned to take the first ax if membership revenues start to follow the economy downward.

There is another concern too. As we have shifted our publication efforts increasingly to online activity, we are increasingly dependent on raiding the cupboards of our print publications for online content. But in the process we are allocating less time to developing and publishing new content, creating what I fear is a diminishing spiral in the amount of content that we can make available online. The long-term consequences of the current tensions in our publishing activities are, therefore, worrisome.

My own growing doubts about the balance between our print and online publishing programs have been exacerbated by the growing spread of a simplistic open-access rhetoric among some in the Association. As scholars, they justifiably believe that they have a moral obligation to ensure that scholarship reaches the widest possible public. But this tends to come attached to a notion that since online publications are cheaper to distribute, the actual costs approach insignificance.

But as the expenses and revenue figures indicate, we have not found a solution to two fundamental problems. First, while the costs for reaching the 100th and the 1,000th reader is reduced almost to zero, the costs for reaching the first reader have actually gone up. And second, it appears that we have entered a point of diminishing returns, not just in creating and channeling so much content and making it available for free, but because simply maintaining the content we already have online has become a growing burden (and cost) of its own. Like Jacob Marley’s chains, link-by-link we forge digital burdens that we can never seem to lay down. The information has to be updated, links fixed, and the technological containers for the data regularly refreshed. We are quickly reaching a point where the content we can make available is being curtailed, and our ability to maintain what we already have is beginning to erode. So despite my best efforts to convince others of these realities, the idealistic enthusiasms of the open-access movement often seem to make such concerns disappear into puffs of fiscal optimism and good intentions.

I also worry that the simplified version of open-access rhetoric that suggests everything digital is cheaper and easier tends to suck the air out of efforts to expand and enrich online scholarship. Our experience with the Gutenberg-e publishing program is a case in point. As regular readers of Perspectives on History will know, the project was intended to identify 36 dissertations in history, and help the authors develop them into models of new electronic scholarship, with generous funding by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

When Robert Darnton originally came up with the idea for this project, he imagined a model that would produce new books that were fundamentally different from the traditional book—with the possibility of multilinear readings and different connections between text and supporting materials. Structurally, the project was developed and staffed at Columbia University with that model in mind.

By the end, however, we discovered it was not really feasible to do this economically, even with the funding from the Mellon Foundation. While the interactions between authors, editors, and technology people were useful, we quickly found that the only way to finish the project within the available resources was to essentially force all the publications into a fairly standard linear template, with other material linked as supplementary.

In many ways, that has been the most eye-opening experience about the constraints on our visions of a digital publishing future, and the resources necessary to get there. It has further heightened my pessimism about the development of future new media projects by a small and underfunded organization like the AHA.

Looking ahead, I have been weighing different strategies to sustain the mission of the organization and the publishing program at the same time. Up to the present we have managed to create a diverse range of products and fulfill the Association’s mission far better than in the middle decades of the past century without doing any actual harm to the organization.

Unfortunately, that seems to leave the publications department in a fairly precarious financial position. The most obvious alternative would be to pull most of our digital content behind a paywall, only allowing access to members and those willing to pay per view. To some extent I think we have to concede that we are largely just a niche organization, and we cannot hope to pay our way through online advertising (which requires a much higher volume of traffic than we appear capable of generating). Given that, I think there is a strong argument to be made for casting up a wall that leaves only a small amount of informational and promotional material out there. However, I am reluctant to do that because I think having more content out there serves the larger goals of the organization.

But the alternatives seem scarce. For the immediate future, we can muddle along, beefing up our print publication program modestly, both to boost revenue and to potentially provide new content for the web site. And over the long term, I am also inclined to believe that our role will gain in significance over time. As the internet becomes increasingly awash in information, I remain optimistic that the islands of certified high-quality information that the AHA represents will become more important—and gain greater appreciation. Whether that appreciation translates into the funds needed to keep our little island afloat remains to be seen.

—Robert Townsend is the AHA’s assistant director for publications and research. This is a shortened version of a presentation given at the international conference of the Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers in September 2008.

Tags: AHA Activities

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.